Search

Socialist Party of Chile

The Socialist Party of Chile (Spanish: Partido Socialista de Chile, or PS) is a centre-left political party founded in 1933. Its historic leader was President of Chile Salvador Allende, who was deposed in a coup d'état by General Augusto Pinochet in 1973. The military junta immediately banned socialist, Marxist and other leftist political parties. Members of the Socialist party and other leftists were subject to violent suppression, including torture and murder, under the Pinochet dictatorship, and many went into exile. Twenty-seven years after the 1973 coup, Ricardo Lagos Escobar won the Presidency as the Socialist Party candidate in the 1999–2000 Chilean presidential election. Socialist Michelle Bachelet won the 2005–06 Chilean presidential election. She was the first female president of Chile and was succeeded by Sebastián Piñera in 2010. In the 2013 Chilean general election, she was again elected president, leaving office in 2018.

History

Beginnings

The Socialist Party of Chile was co-founded on 19 April 1933, by Colonel Marmaduque Grove, who had already led several governments, Oscar Schnake, Carlos Alberto Martínez, future President Salvador Allende, and other personalities. After the Chilean coup of 1973 it was proscribed (along with the other leftist parties constituting the Popular Unity coalition) and the party split into several groups which would not reunite until after the return to civilian rule in 1990.

Socialist thought in Chile goes back to the mid-19th century, when Francisco Bilbao and Santiago Arcos opened a debate on civil rights and social equality in Chile. These ideas took hold in the labour movement at the beginning of the 20th century and, along with them, the various communist, anarchist, socialist, and mutualist ideals of the time were diffused by writers and leaders such as Luis Emilio Recabarren. The impact of the 1917 October Revolution in Russia imparted new vigor to Chile's revolutionary movements, which in the 1920s were mostly identified with the global Communist movement; the Communist Party of Chile was formed.

The Great Depression in the 1930s plunged the country's working and middle classes into a serious crisis that led them to sympathize with socialist ideas, which found expression in the establishment of the short-lived Socialist Republic of Chile in 1932. The idea of founding a political party to unite the different movements identified with socialism took shape in the foundation of the Socialist Party of Chile, on 19 April 1933. At a conference in Santiago, at 150 Serrano, 14 delegates from the Socialist Marxist Party led by Eduardo Rodriguez Mazer; 18 from the New Public Action, headed by the lawyer Eugenio Matte Stolen; 12 delegates of the Socialist Order, whose main exponent was the architect Arturo Bianchi Gundian; and 26 representatives of the Revolutionary Socialist Action of Óscar Schnake formulated the new party's founding document and its short-term action plan, and elected Óscar Schnake as its first executive Secretary General.

The Party's Statement of Principles was:

- The Socialist Party embodies Marxism, enriched by scientific and social progress.

- The Capitalist exploitation based on the doctrine of private property regarding land, industry, resource, and transportation, necessarily must be replaced by an economically socialist state in which said private property be transformed into collective.

- During the process of total transformation of the system of government, a representative revolutionary government of the manual and intellectual labourers' class is necessary. The new socialist state only can be born of the initiative and the revolutionary action of the proletariat masses.

- The socialist doctrine is of an international character and requires the support of all the workers of the world. The Socialist Party will support their revolutionary goals in economics and politics across Latin America in order to pursue a vision of a Confederacy of the Socialist Republics of the Continent, the first step toward the World Socialist Confederation.

The Party quickly obtained popular support. Its partisan structure exhibits some singularities, such as the creation of "brigades" that group their militants according to environment of activity; brigades that live together organically, and brigades of militant youths such as the Confederacy of the Socialist Youth, and the Confederacy of Socialist Women. In the later 1930s they included the "Left Communist" faction, formed by a split of the Communist Party of Chile, headed by Manuel Noble Plaza and comprising the journalist Oscar Waiss, the lawyer Tomás Chadwick and the first secretary of the PS, Ramón Sepúlveda Loyal, among others.

In 1934, the Socialists, along with the Radical-Socialist Party and the Democratic Party, formed the "Leftist Bloc". In the first parliamentary election (March 1937) they obtained 22 representatives (19 representatives and 3 senators), among them its Secretary general Oscar Schnake Vergara, elected senator of Tarapacá-Antofagasta, placed by the PS in a noticeable place inside the political giants of the epoch. For the 1938 presidential election, the PS participated in the formation of the Popular Front, withdrawing its presidential candidate, the colonel Marmaduque Grove, and supporting the Radical Party's candidate, Pedro Aguirre Cerda, who narrowly defeated the right-wing candidate following an attempted coup by the National Socialist Movement of Chile. In the government of Aguirre Cerda the socialists obtained the Ministries of Public Health, Forecast and Social Assistance, given to Salvador Allende, the Minister of Promotion, trusted to Oscar Schnake, and the Ministers of Lands and Colonization, handed out to Rolando Merino.

The participation of the Socialist Party in the government of Aguirre Cerda reached an end on 15 December 1940, due to internal conflicts among the Popular Front coalition, in particular with the Communist Party. In the parliamentary elections of March 1941 the PS advanced outside of the Popular Front and obtained 17,9% of the votes, 17 representatives and 2 senators. The PS integrated into the new leftist coalition following Cerda's death, now named Democratic Alliance, which supported the candidacy of the Radical Juan Antonio Ríos, who was triumphantly elected. The Socialists participated in his cabinet, alongside Radicals, members of the Democratic Party and of the Liberal Party and even of the Falange. Oscar Schnake occupied once again the post of Promotion and the socialist Pedro Populate Vera and Eduardo Escudero Forrastal assumed the positions of Lands and Colonization and Social Assistance, respectively.

The youth of the party assumed a very critical attitude toward these changes and mergers, which caused the expulsion of all the Central Committee of the FJS, among them Raúl Vásquez (its secretary general), Raúl Ampuero, Mario Palestro and Carlos Briones. In the IX Congress of the PS of the year 1943 Salvador Allende displaced Marmaduque Grove as Secretary General and withdrew his party from the government of Ríos. Grove did not accept this situation, and was expelled from the PS and formed the Authentic Socialist Party. These conflicts caused the PS to drop violently to only 7% of the votes in the parliamentary elections of March 1945, diminishing significantly its parliamentary strength.

After World War II

There was complete confusion in the Socialist Party for the presidential election of 1946. The PS decided to put up its own candidate; its secretary general Bernardo Ibáñez. However, many militants supported the radical candidate Gabriel González Videla, while the Authentic Socialist Party of Grove stopped supporting the liberal Fernando Alessandri.

After the failure of the candidacy of Ibáñez (who obtained barely a 2.5% of the votes), the purges continued. In the XI Ordinary Congress the current "revolution" of Raúl Ampuero was imposed and he assigned to academic Eugenio González the making of the Program of the Socialist Party which defined its north; the Democratic Republic of Workers.

The promulgation, in 1948, of the Law 8.987 "Defense of Democracy Law" that banned the communists, was again a factor of division among the socialists. Bernardo Ibáñez, Oscar Schnake, Juan Bautista Rosseti and other anticommunist socialists supported it with enthusiasm; while the board of directors of the party directed by Raúl Ampuero and Eugenio González rejected it. The anticommunist group of Ibáñez was expelled from the PS and they constituted the Socialist Party of the Workers; nevertheless the Conservative of the electoral Roll assigned to the group of Ibáñez the name Socialist Party of Chile, forcing the group of Ampuero to adopt the name Socialist Popular Party.

The Socialist Popular Party proclamation, in its XIV Congress, carried out in Chillán in May 1952, as its presidential standard bearer to Carlos Ibáñez del Campo, despite the refusal of the senators Salvador Allende and Tomás Chadwick. Allende abandoned the party and united the Socialist Party of Chile, which, as a group with the Communist Party (outlawed), raised the candidacy of Allende for the Front of the People. The triumph of Ibáñez permitted the popular socialists to have important departments such as that of Work (Clodomiro Almeyda) and Estate (Felipe Herrera).

After the parliamentary elections of 1953; where the Socialist Popular Party obtained 5 senators and 19 representatives, the popular socialists abandoned the government of Carlos Ibáñez del Campo and proclaimed the need to establish a Front of Workers, in conjunction with the Democratic Party of the People, the socialists of Chile and the outlawed communists.

Finally, on 1 March 1956, the two socialist parties (Socialist Party of Chile and Socialist Popular Party), the Party of the Workers (communist outlawed), Democratic Party of the People and the Democratic Party all signed the minutes of constitution of the Front of Popular Action (FRAP) with Salvador Allende Gossens as the president of the coalition, which participated successfully in the municipal elections of April 1956.

After the parliamentary elections of March 1957 the "Congress of Unity" was carried to power, formed from the Popular Socialist Party directed by Rául Ampuero and the Socialist Party of Chile of Salvador, directed by Allende Gossens. These chose the secretary general of the unified Socialist Party; Salomón Corbalán.

On 31 July 1958, the Law of Permanent Defense of Democracy was derogated by the National Congress, therefore the ban of the Communist Party was repealed. In the presidential elections of 1958, the standard bearer of the Front of Popular Action (FRAP), the socialist Salvador Allende, lost the presidential election narrowly to Jorge Alessandri. In spite of the loss, the unification of the socialist parties had a new leader, and Chile was one of the few countries of the world in which a Marxist had clear possibilities to win the presidency of the Republic through democratic elections.

The overwhelming triumph of Eduardo Frei Montalva over the candidate of the FRAP Salvador Allende Gossens in the presidential elections of September 1964 caused demoralization among the followers of the "Chilean way to socialism". The National Democratic Party (PADENA) abandoned the coalition of left; and the influence of the Cuban revolution and above all of the "guerrilla way of Ernesto Guevara" they were left to feel the heart of the Socialist Party. The discrepancies of the party were perceived clearly. In July from 1967 the senators Raúl Ampuero and Tomás Chadwick and the representatives Ramón Silva Ulloa, Eduardo Osorio Pardo and Oscar Naranjo Arias were expelled, and founded the popular socialist union (USOPO).

In the XXII Congress, which took place in Chillán in November 1967, the political became more radical, under the influence of Carlos Altamirano Orrego and the leader of the Ranquil Rural Confederation, Rolando Calderón Aránguiz. The party now officially adhered to Marxism-Leninism, declared itself in favour of revolutionary, anticapitalist and anti-imperialist changes.

Popular Unity government

In 1969, skepticism about the "Chilean way to socialism" prevailed in the Central Committee of the Socialist Party. Salvador Allende Gossens was proclaimed as the party's presidential candidate, with 13 votes in favor and 14 abstentions, among them that of its secretary general, Aniceto Rodriguez, of Carlos Altamirano Orrego, and of Clodomiro Almeyda Medina. Nevertheless, the candidacy of Allende galvanized the forces of the left, who formed, in October 1969, the Popular Unity coalition including the Socialist Party, Communist Party, Radical Party, Popular Unitary Action Movement (which had split from the Christian Democrat Party), and Independent Popular Action, consisting of former supporters of Carlos Ibáñez. Popular Unity triumphed in the presidential election of September 1970.

On 24 October 1970 Salvador Allende Gossens was officially proclaimed President of the Republic of Chile. There was world expectation; he agreed to manage the coalition and to be a Marxist president with the explicit commitment to build socialism, while respecting the democratic and institutional mechanisms.

The position of the PS on joining the government of the UP became more radical when senator Carlos Altamirano Orrego took over as party leader, having been elected at the XXIII Congress in La Serena in January 1971. He proclaimed that the party should become "the Chilean vanguard in the march toward socialism".

In the municipal elections of April 1971, the leftist coalition achieved an absolute majority in the election of local councillors, which caused growing polarization due to the alliance of the Christian Democrats with the sectors of the right in the country. The withdrawal of the Party of Radical Left from the government, with its 6 representatives and 5 senators, meant that the government of Allende was left with less than one third of both houses of the parliament.

In the parliamentary elections of March 1973, the Popular Unity ruler coalition managed to block a move by the opposing Democratic Confederation to impeach Allende. This initiative did not attain the required two-thirds majority.

Coup d'état and political suppression

The serious economic problems facing the government only deepened the country's political divisions. The Socialist Party, which had posted its highest electoral showing in history, was opposed, along with MAPU, to any dialogue with the right-wing opposition. Meanwhile, from the United States, a concerted plan was underway to prevent socialists from gaining power around the world, including CIA backing for the right wing in Chile. On 11 September 1973, Augusto Pinochet led the military coup against Allende's government, putting an end to the Presidential Republic Era begun in 1924. President Salvador Allende refused to relinquish power to the Armed Forces, and ultimately committed suicide in his office at the Palace of La Moneda, during an intensive air bombardment of the historic edifice.

The military coup d'état was devastating to the organization of the Chilean Socialist Party. Within a few weeks of the coup, four members of their Central Committee and seven regional secretaries of the Partido Social had been murdered. A further twelve members of the Central Committee were imprisoned, while the remaining members took refuge in various foreign embassies. The Socialist Party's Secretary General, Carlos Altamirano, managed to escape from Chile, appearing in Havana on 1 January 1974, during the anniversary of the Cuban Revolution.

Lack of experience working 'underground' during the ban led to the breakup of the Party's Secret Directorate. The secret services of the military state managed to infiltrate the organization and, one by one, arrested its principal leaders. The bodies of Exequiel Ponce Vicencio, Carlos Lorca Tobar (disappeared 1975), Ricardo Lagos Salinas and Víctor Zerega Ponce were never found.

Other victims of repression were the former home Secretary, José Tohá González and the former Minister of National Defense, Orlando Letelier del Solar. Having reviewed the consequences of the defeat of the Unidad Popular, and observed the experiences of refugees of "true socialism" in Eastern Europe, and seeing the lack of a cohesive strategy to continue against Pinochet's regime, there was deep dissent within its exterior organization, whose central management was in the German Democratic Republic.

In April 1979, the Tercer Pleno Exterior, the majority sector of the party, named Clodomiro Almeyda as the new Secretary General, Galo Gómez as the Assistant Secretary and expelled Carlos Altamirano, Jorge Arrate, Jaime Suaréz, Luis Meneses and Erich Schnake from the party, charging them with being "remnants of a past which is in the process of being overcome who testify to the survival of a nucleus which is irreducible and resistant to the superior qualitative development of a true revolutionary vanguard".

Altamirano, not accepting this, declared a re-organization of the party and called a Conference. The XXIV Conference took place in France in 1980 and Altamirano declared there that, "Only a very deep and rigorous renewal of definitions and proposals for action, language, style and methods of "doing politics" will make our revolutionary action effective (...) It does not force us to "relaunch" the Partido Social (Socialist Party) of Chile. Yes, it means we must "renew it", understand it as our most precious instrument of change, as an option for power, as an alternative to transformation."

1980s reemergence under dictatorship

In the 1980s socialist factions reemerged as active opponents to the Pinochet government. A sector, from among the so-called "renewed socialist", founded the Convergencia Socialista (the Socialist Convergence), which contributed to the Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitaria – MAPU (Unified Movement of Popular Action), the peasant worker MAPU, and the Christian Leftists. They aimed, in conjunction with the Christian Democracy, to end dictatorship through "non-disruptive methods". The other sector (majority from among the socialist militants in the interior of the country) formed the "popular rebellion" alliance – an agreement with the Communist Party, the Leftist Revolutionary Movement and the Radical Party of Anselmo Sule. The objectives were the same. After the First National Protest against the Pinochet regime, which occurred on 11 May 1983, the efforts of the different factions of the Socialist Party intensified.

The XXIV ("renewed") Socialist Party Congress, directed by Ricardo Ñúnez, decided to form the Democratic Alliance. This was a coalition of Christian Democrats, Silva Cimma radicals, and sectors from the republican and democratic right wing. They convened the Fourth National Protest Day (11 August 1983) and proposed, in September 1983, the formation of the Socialist Bloc, the first attempt at a unification of Chilean socialism under the slogan "Democracy Now!".

In the meantime, the "Almeyda" Partido Social, in conjunction with the Communist Party, Aníbal Palm radicals and the Leftist Revolutionary Movement, founded the "Movimiento Democrático Popular" (MDP) (Popular Democratic Movement) on 6 September 1983, which caused the Fifth Day of National Protest.

The signing of the National Accord in late August 1985, between the Democratic Alliance and sectors of the right wing aligned to the military regime, deepened divisions among the Chilean left wing. The most radical politico-military arm opposed the method of gradual transition towards democracy. Their primary exponent was the Frente Patriótico Manuel Rodríguez (FPMR) (the Manuel Rodriguez Patriotic Front).

The MAPU-OC, whose main figures were Jaime Gazmuri, Jorge Molina and Jaime Estévez, was added to the "renewed" Partido Social, now directed by Carlos Briones.

In September 1986, the politico-military method of "mass violent insurrectionist uprisings" was finally aborted after the failure of "Operation 20th century", as the assassination attempt on Pinochet by the FPMR was called. Some of the top leaders from among the revolutionary sectors of the "Almeyda" Partido Social, along with conciliators and opportunists, on realizing that the idea of overthrowing the dictatorship was not a viable strategy, began to take control of the party and distance themselves from the Communist Party. As a result, the socialist left wing realized that a "negotiated solution" to the conflict could not be found outside of the provisions of the 1980 Constitution.

In March 1987, Clodomiro Almeyda entered Chile secretly and presented himself before the court to rectify his situation. He was deported to Chile Chico, condemned and deprived of his civic rights.

In April 1987, Ricardo Núñez, new leader of the "renewed" Partido Social, announced, at the 54th Anniversary of the party, "We are not going to remove Pinochet from the political scene using weapons. We shall defeat him with the ballot boxes (..) We are convinced that the town is going to stop Pinochet with the ballot boxes. We are going to build that army of seven million citizens to embrace different alternatives to the Chilean political landscape."

In December 1987 the "renewed" Partido Social founded the Partido por la Democracia (PPD) (Party for Democracy), an "instrumental" party serving as a tool to enable legally democratic forces to participate in the 1988 Plebiscite (Referendum) and in subsequent elections. Ricardo Lagos was appointed as the president. Some radicals, dissident communists, and even democratic liberals joined this party.

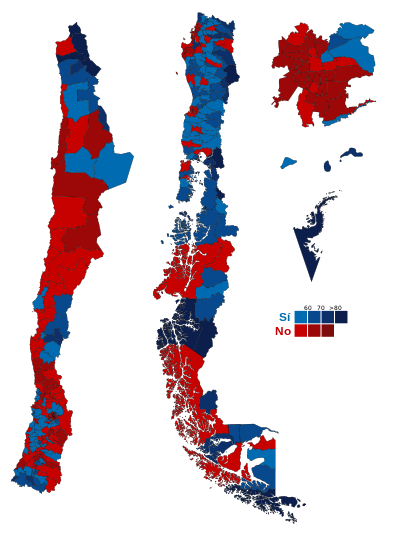

In February 1988 the Concertación de Partidos por el No (Coalition of Parties for the 'No') was formed. 17 political parties and movements in Chile joined this coalition. Among them were the members of the Alianza Democrática (the Democratic Alliance), the Almeyda Partido Social, and the Christian Left. The political direction of the campaign fell on the Christian Democratic leader, Patricio Aylwin, and Ricardo Lagos from the PPD. They achieved successful results in the 5 October 1988, Plebiscite, where close to 56% of the valid votes cast rejected the idea that Pinochet would continue as the President of the Republic.

After the October 1988 Plebiscite, the Concertación called for constitutional reform to remove the "authoritarian clauses" of the 1980 Constitution. This proposal by the democratic opposition was partly accepted by the authoritarian government via the 30 July 1989, Plebiscite, where 54 reforms to the existing Constitution were approved. Among these reforms were the revocation of the controversial article 8, which served as the basis for the exclusion of the socialist leader, Clodomiro Almeyda, from political involvement.

In November 1988 the Almeyda Partido Social, the Christian Left and the Communist Party, among other left wing organizations, formed an "instrumental" party called Partido Amplio de Izquierda Socialista (PAIS) (the Broad Left Socialist Party), with Luis Maira as the president and Ricardo Solari as the secretary general.

Concertación

In May 1989, the "renewed" PS held internal elections by secret ballot by its nationwide membership, for the first time in the history of Chilean socialism. The list composed of Jorge Arrate and Luis Alvarado won, against the competing lists of Erich Schnake and Akím Soto, and of Heraldo Muñoz (supported by Ricardo Lagos' faction within the party).

The winning list of Jorge Arrate represented the tendency of the "socialist renewal", upholding a permanent alliance with the Christian Democrats within the Concertación, and strongly defending the unity of the party, in contrast to other internal tendencies. After the elections the XXV Congress was convoked at Costa Azul, which took the momentous decision for Chilean socialism to abandon its traditional isolationism and join the Socialist International.

In June 1989, the Concertación appointed the Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin as its standard bearer for the presidential elections. Aylwin had beaten Gabriel Valdés and Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle in the party's internal elections, and a few weeks before the election he received the support of the radicals of Silva Cimma and even of the former Almeyda supporters (PS-Almeyda). Finally the PS-Arrate (or "renewal" PS) dropped its candidate Ricardo Lagos and added itself to the candidacy of Aylwin, who as president of the Christian Democratic Party was one of the main opponents of the Popular Unity government.

Aylwin won easily in the presidential elections of 1989, gaining more than the 55% of the valid votes. "Renewal Socialism" was strengthened as 16 representatives of the PPD were elected, 13 of whom were members of the PS-Arrate. In the matter of senators, three of their members were chosen (Ricardo Núñez Muñoz, Jaime Gazmuri and Hernán Vodanovic), but there was regret over the rout of Ricardo Lagos in his candidacy of Santiago West.

PS-Almeyda obtained seven representatives, two of them standing for the PAIS, and the other five elected as independents within the Concertación list. Rolando Calderon Aránguiz was elected as senator in Magallanes.

The fall of the wall of Berlin, on 9 November 1989, deeply affected the Chilean left, especially in its more orthodox sector. This accelerated the process of unification within the party, which was finalized on 27 December 1989. The Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitaria, led by Oscar Guillermo Garretón, took this chance to join the united PS.

Between 22 and 25 November 1990 the "Salvador Allende Unity Congress" was held, with past leaders such as Raúl Ampuero and Aniceto Rodriguez and the Christian Left headed by its president Luis Maira and its two representatives (Sergio Aguiló and Jaime Naranjo) joining the party. In that Congress Jorge Arrate was chosen as president, Ricardo Núñez Muñoz as vice president and Manuel Almeyda Medina as secretary general.

Hortensia Bussi, the widow of Allende, sent a message to the Congress from Mexico:

I salute with deep feeling the reunification of the Socialist Party of Chile. You all know how I have waited for this moment, certain that Allende's comrades would overcome their differences and rebuild the powerful democratic left that Chile needs.

The first challenges for the unified socialists were the exercise of power and the "double membership" status of the "renewal socialists" as members of both the PS and the PPD. Finally, the Socialist Party decided to have itself recorded under its own name and symbols in the electoral rolls, and gave a two-year time limit to its members to opt for the PS or the PPD. A significant number of "renewal socialists" did not return to the PS; among them Erich Schnake, Sergio Bitar, Guido Girardi, Jorge Molina, Vicente Sotta, Víctor Barrueto and Octavio Jara.

In power, the socialists Enrique Correa (as the minister General Secretary of Government), Carlos Ominami (Economy), Germán Correa (Transportation), Ricardo Lagos and Jorge Arrate (Education) and Luis Alvarado (National Resources) entered the cabinets of President Aylwin, while in the House of Representatives, the socialists José Antonio Viera-Gallo and Jaime Estevéz exercised its presidency.

In the elections of 1992, Germán Correa was chosen as president of the PS, supported by the "renewal" group around Ricardo Núñez Muñoz and the "third way" faction within the Almeyda tendency. They prevailed against Camilo Escalona, Clodomiro Almeyda and Jaime Estevez, representing an alliance between the traditional supporters of Clodomiro Almeyda and one faction of Jorge Arrate's "renewal" tendency.

Concertación under Christian Democrat leadership (1990–2000)

The left (PS-PPD) backed Ricardo Lagos as the Concertación candidate for the 1993 presidential elections, but he was defeated by the Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle, gaining only 36.6% of the vote in the primary on 23 May. After Frei became president, the Socialists took up senior posts in his first cabinet: Interior (Germán Correa), Planining (Luis Maira), Labor (Jorge Arrate), and Public Works (Ricardo Lagos).

In the parliamentary elections of December 1997, the PS did badly: its deputies decreased from 16 to 11, and its senators from 5 to 4. Its senatorial candidate Camilo Escalona obtained a mere 16% of the vote in Santiago West.

The detention of Pinochet in London in October 1998 caused tensions within the PS. The Socialist foreign affairs ministers José Miguel Insulza and Juan Gabriel Valdés pressed to have the ex-dictator returned to Chile, while a group of leading Socialists including Isabel Allende Bussi, Juan Pablo Letelier, Fanny Pollarolo and Juan Bustos Ramírez travelled to London to support judge Baltasar Garzón's proceedings for extradition to Spain.

Leading up to the 1999 presidential elections, the PS, PPD and Radical Social-Democratic Party again supported Lagos as candidate. This time Lagos won the primary on 30 May, with 70.2% of votes. In the general election, he won 48.0% in the first round of voting and was elected with 51.3% in the second round.

Despite the party having been reunified in 1990 the Socialist Party had five internal factions; Nueva Izquierda, Generacional, Tercerismo, Arratismo and Nuñismo. By 1998 Arratismo and Nuñismo had merged into Megatendencia while Generacional, a brief tendency called Almeydismo and elements of Nueva Izquierda had merged into Colectivo de Identidad Socialista. Nueva Izquierda and Tercerismo remained as relatively stable factions by 1998.

Concertación under Socialist governments (2000–2010)

Lagos was elected president in 1999, defeating the rightwing candidate Joaquín Lavín with 51.3% of the vote, thus becoming the first president in thirty years to have Socialist support – even though Lagos himself was a PD member. Socialist ministers in his first cabinet were José Miguel Insulza (Interior), Ricardo Solari (Labor), Carlos Cruz (Public Works), and Michelle Bachelet (Health).

In the 2001 Chilean parliamentary election, as part of the Coalition of Parties for Democracy, the party won 10 out of 117 seats in the Chamber of Deputies of Chile and 5 out of 38 elected seats in the Senate. The 2001 parliamentary elections were a setback for the Socialists and for the Concertación as a whole. The PS increased its representation by only one deputy and one senator, while the Concertación vote sank below 50% for the first time in its existence.

In September 2003, marking 30 years since the coup against Allende, the Socialist Party issued a document accepting responsibility for the events:

It is beyond all doubt that President Allende maintained an unchanging and impeccable attitude (...) Nevertheless, the socialists have made it clear, and we repeat it now, that we did not do enough to defend the democratic regime. We aimed to carry through a program of change without the necessary majorities in parliament and in society, we remained intransigent in the matter, and we did not give President Allende the support of his party that he needed to lead the government along the pathways that had been defined.

The outcome of the 2005 parliamentary elections was favorable both for the Socialists and for the Concertación: the PS increased its deputies from 12 to 15, and its senators from 5 to 8, giving it the largest block it had ever had in the Senate. Moreover, Michelle Bachelet was elected as president of Chile. For its part, the Concertación regained its electoral hegemony, with an absolute majority in both chambers of parliament.

Bachelet took over as president on 11 March 2006. She was the first woman president in the country's history, and the fourth successive president from the Concertación. Her initially high popularity dropped considerably as a result of the 2006 student mobilization known as the "Penguin Revolution", the Transantiago crisis, and various conflicts within the governing coalition. Described as a "social contract", her government reformed pensions and the social security system, aiming to help thousands of Chileans to improve their quality of life. Her government had to confront the world economic crisis of 2008, but her popularity figures recovered as Chileans formed a positive opinion of her leadership, and her final approval rating of 84% had never before been attained by any Chilean head of state on leaving their post.

Within the Party, divisions widened, with dissident factions opposing the policy of Camilo Escalona. Prominent figures including Jorge Arrate, senator Alejandro Navarro and deputy Marco Enriquez-Ominami quit the party in 2008 and 2009.

In the 2009 parliamentary elections, the PS led by Escalona suffered a serious defeat: it lost its dominance of the Senate, holding just 5 seats, and its deputies reduced in number form 15 to 11. Meanwhile, in new presidential elections, the Concertación candidate Eduardo Frei lost to the rightwinger Sebastián Piñera, putting an end to twenty years of Concertación rule.

Nueva Mayoría

Michelle Bachelet won the second round of the 2013 Chilean presidential election with 62% of the votes. She was the candidate of Nueva Mayoría ("New Majority"), a broadened version of the Concertación now including the Communist Party and others.

Presidents elected

- 1970 – Salvador Allende

- 2000 – Ricardo Lagos (with dual membership in the Party for Democracy)

- 2006 – Michelle Bachelet

- 2014 – Michelle Bachelet

Election results

Due to its membership in the Concert of Parties for Democracy, the party has endorsed the candidates of other parties on several occasions. Presidential elections in Chile are held using a two-round system, the results of which are displayed below.

Presidential elections

See also

- Government Junta of Chile (1973)

- Human rights violations in Pinochet's Chile

- Víctor Olea Alegria, disappeared in 1974

- Carlos Lorca, disappeared in 1975

- Carlos Altamirano, general secretary between 1971 and 1979

- Chamber of Deputies of Chile Resolution of 22 August 1973

References

External links

- Partido Socialista de Chile (in Spanish)

- Declaración de Principios del Partido Socialista de Chile (in Spanish)

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Socialist Party of Chile by Wikipedia (Historical)

- français (french)

- anglais (english)

- espagnol (spanish)

- portugais (portuguese)

- italien (italian)

- basque

- roumain (romanian)

- allemand (german)

- néerlandais (dutch)

- danois (danish)

- suédois (swedish)

- norvégien (norwegian)

- finnois (finnish)

- letton (lettish)

- lituanien (lithuanian)

- estonien (estonian)

- polonais (polish)

- tchèque (czech)

- bulgare (bulgarian)

- ukrainien (ukrainian)

- russe (russian)

- grec (greek)

- serbe (serbian)

- croate (croatian)

- arménien (armenian)

- kurde (kurdish)

- turc (turkish)

- arabe (arabic)

- hébreu (hebrew)

- persan (persian)/farsi/parsi

- chinois (chinese)

- japonais (japanese)

- coréen (korean)

- vietnamien (vietnamese)

- thaï (thai)

- hindi

- sanskrit

- urdu

- bengali

- penjabi

- malais (malay)

- cebuano (bisaya)

- haoussa (hausa)

- yoruba/youriba

- lingala

Partido Socialista

Partido Socialista is Spanish and Portuguese for "Socialist Party". Used as a proper noun without any other adjectives, it may refer to:

- Socialist Party (Argentina)

- Socialist Party (Bolivia, 1971)

- Socialist Party of Chile

- Socialist Party (Guatemala)

- Socialist Party (Panama)

- Socialist Party (Peru)

- Socialist Party (Portugal)

- Socialist Party of Uruguay

- Partido Socialista de Puerto Rico

- Partido Socialista Puertorriqueño

See also

- List of socialist parties

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Partido Socialista by Wikipedia (Historical)

- français (french)

- anglais (english)

- espagnol (spanish)

- portugais (portuguese)

- italien (italian)

- basque

- roumain (romanian)

- allemand (german)

- néerlandais (dutch)

- danois (danish)

- suédois (swedish)

- norvégien (norwegian)

- finnois (finnish)

- letton (lettish)

- lituanien (lithuanian)

- estonien (estonian)

- polonais (polish)

- tchèque (czech)

- bulgare (bulgarian)

- ukrainien (ukrainian)

- russe (russian)

- grec (greek)

- serbe (serbian)

- croate (croatian)

- arménien (armenian)

- kurde (kurdish)

- turc (turkish)

- arabe (arabic)

- hébreu (hebrew)

- persan (persian)/farsi/parsi

- chinois (chinese)

- japonais (japanese)

- coréen (korean)

- vietnamien (vietnamese)

- thaï (thai)

- hindi

- sanskrit

- urdu

- bengali

- penjabi

- malais (malay)

- cebuano (bisaya)

- haoussa (hausa)

- yoruba/youriba

- lingala

Christian Democratic Party (Chile)

The Christian Democratic Party (Spanish: Partido Demócrata Cristiano, PDC) is a Christian democratic political party in Chile. There have been three Christian Democrat presidents in the past, Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle, Patricio Aylwin, and Eduardo Frei Montalva.

Customarily, the PDC backs specific initiatives in an effort to bridge socialism and laissez-faire capitalism. This economic system has been called "social capitalism" and is heavily influenced by Catholic social teaching or, more generally, Christian ethics. In addition to this objective, the PDC also supports a strong national government while remaining more conservative on social issues. However, after Pinochet's military regime ended the PDC embraced more classical economic policies compared to before the dictatorship. The current Secretary-General of the PDC is Gonzalo Duarte. In their latest "Ideological Congress", the Christian Democrats criticized Chile's current economic system and called for a shift toward a social market economy (economía social de mercado). The PDC had cooperated with centre-left parties after the end of Pinochet rule.

Except during the military dictatorship (1973–1990) when the congress was shut down the Christian Democrat Party was the largest party in parliament from 1965 to 2001. In 2022 the party has faced a severe internal crisis, with many prominent politicians leaving it.

History

The origins of the party go back to the 1930s, when the Conservative Party split between traditionalist and social-Christian sectors. In 1935, the social-Christians split from the Conservative Party to form the Falange Nacional (National Phalanx), a more socially oriented and centrist group.

The Falange Nacional showed their centrist policies by supporting leftist Juan Antonio Ríos (Radical Party of Chile) in the 1942 presidential elections but Conservative Eduardo Cruz-Coke in the 1946 elections. Despite the creation of the Falange Nacional, many social-Christians remained in the Conservative Party, which in 1949 split into the Social Christian Conservative Party and the Traditionalist Conservative Party. On July 28, 1957, primarily to back the presidential candidacy of Eduardo Frei Montalva, the Falange Nacional, Social Christian Conservative Party, and other like-minded groups joined to form the Christian Democratic Party. Frei lost the elections, but presented his candidacy again in 1964, this time also supported by the right-wing parties. That year, Frei triumphed with 56% of the vote. Despite right-wing backing for his candidacy, Frei declared his planned social revolution would not be hampered by this support.

In 1970, Radomiro Tomic, leader of the left-wing faction of the party, was nominated to the presidency, but lost to socialist Salvador Allende. The Christian Democrat vote was crucial in the Congressional confirmation of Allende's election, since he had received less than the necessary 50%. Although the Christian Democratic Party voted to confirm Allende's election, they declared themselves as part opposition because of Allende's economic policy. By 1973, Allende had lost the support of most Christian Democrats (except for Tomic's left-wing faction), some of whom even began calling for the military to step in. By the time of Pinochet's coup, most Christian Democrats applauded the military takeover, believing that the government would quickly be turned over to them by the military. Once it became clear that Pinochet had no intention of relinquishing power, the Christian Democrats went into opposition. During the 1981 plebiscite where Chilean voted to extend Pinochet's term for eight more years, Eduardo Frei Montalva led the only authorized opposition rally. When political parties were legalized again, the Christian Democratic Party, together with most left-wing parties, agreed to form the Coalition of Parties for the No, which opposed Pinochet's reelection on the 1988 plebiscite. This coalition later became Coalition of Parties for Democracy once Pinochet stepped down from power and held together until 2010s.

Transition to democracy

During the first years of the return to democracy, the Christian Democrats enjoyed wide popular support. Presidents Patricio Aylwin and Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle were both from that party, and it was also the largest party in Congress. However, the Christian Democrat Andrés Zaldívar lost the Coalition of Parties for Democracy 1999 primaries to socialist Ricardo Lagos. In the parliamentary elections of 2005, the Christian Democrats lost eight seats in Congress, and the right-wing Independent Democratic Union became the largest party in the legislative body. The Christian Democrats lost its influence to the socialists after Michelle Bachelet became president.

For much of the 1990s and 2000s the party contained three main factions; "Guatones", "Chascones" and "Colorines" (lit. Fatsos, Disheveleds and Redheads). The Colorines owed their name to the hair color of Adolfo Zaldívar and were the right-wing faction of the party. The Chascones led by Gabriel Silber and Gabriel Ascencio were the left-wing faction and the Guatones owed their label for being "close to power" through the figures of Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle and Patricio Aylwin, both of them Presidents of Chile.

In recent years, the Christian Democrats have favored abortion in three cases (when a pregnancy threatens the mother's life, when the fetus has little chance of survival, and when the pregnancy is a result of rape), but not in any other instances, and opposes elective abortion.

The Christian Democrats left the Nueva Mayoría coalition on 29 April 2017 and nominated then-party president Carolina Goic as their candidate for the 2017 presidential election. The Nueva Mayoria has struggled to remain united as differences have opened up within the coalition over approaches to a government reform drive, including changes to the labour code and attempted reform of Chile's strict abortion laws. In 2020, all Christian Democrats senators voted in favour of same-sex marriage.

in 2020 the party gave its support for "Approve" in the 2020 Chilean national plebiscite.

After the 2019–2021 Chilean protests most of La Nueva Mayoria including the PDC regrouped to form Constituent Unity and participated in the 2021 constitutional convention election (as The Approval List) and the 2021 gubernatorial elections.

After those elections the group renamed to New Social Pact to participate in the 2021 general election, PDC senator Yasna Provoste was chosen as the coalition's candidate, coming in 5th place with 11.6% of the vote. After she lost the first round the PDC supported Gabriel Boric for the second round, in which Boric won the election.

After Boric won the election, most of the New Social Pact parties supported joining Boric's government, on the other hand the Christian Democrat's president, Ximena Rincon, said that the party would be a "constructive opposition" and said that any member joining the government should have to resign to the party. After this the PDC was excluded from the new coalition "Democratic Socialism".

2022 crisis

The official support of the party for the "Approve" option in the 2022 Chilean national plebiscite has led a severe internal division, with various members openly supporting the "Reject" option and subsequent calls for them to be expelled. Some historic figures, like René Cortázar, Soledad Alvear, Gutenberg Martínez and José Pablo Arellano left the party by their own initiative to join Cristián Warnken's Amarillos movement. Ximena Rincón and Matías Walker left the party in October 2022 to form the political movement Demócratas together with Carlos Maldonado and others. Also in October, Governor of Santiago Metropolitan Region Claudio Orrego left the party.

Fuad Chahín, who was president of the party from 2018 to 2021, was suspended from the party in early November 2022.

Presidents elected under Christian Democratic Party

- Eduardo Frei Montalva (1964–1970)

- Patricio Aylwin (1990–1994)

- Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle (1994–2000)

Presidential candidates

The following is a list of the presidential candidates supported by the Christian Democratic Party. (Information gathered from the Archive of Chilean Elections).

- 1958: Eduardo Frei Montalva (lost)

- 1964: Eduardo Frei Montalva (won)

- 1970: Radomiro Tomic (lost)

- 1988 plebiscite: "No" (won)

- 1989: Patricio Aylwin (won)

- 1993: Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle (won)

- 1999: Ricardo Lagos (won)

- 2005: Michelle Bachelet (won)

- 2009: Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle (lost)

- 2013: Michelle Bachelet (won)

- 2017: Carolina Goic (lost) Second round support: Alejandro Guillier (lost)

- 2021: Yasna Provoste (lost) Second round support: Gabriel Boric Font (won)

Election results

References

Further reading

- Luna, Juan Pablo; Monestier, Felipe; Rosenblatt, Fernando (2014). Religious parties in Chile: The Christian Democratic Party and the Independent Democratic Union. Routledge. pp. 119–137.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

External links

Media related to Christian Democrat Party of Chile at Wikimedia Commons

- Official web site

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Christian Democratic Party (Chile) by Wikipedia (Historical)

- français (french)

- anglais (english)

- espagnol (spanish)

- portugais (portuguese)

- italien (italian)

- basque

- roumain (romanian)

- allemand (german)

- néerlandais (dutch)

- danois (danish)

- suédois (swedish)

- norvégien (norwegian)

- finnois (finnish)

- letton (lettish)

- lituanien (lithuanian)

- estonien (estonian)

- polonais (polish)

- tchèque (czech)

- bulgare (bulgarian)

- ukrainien (ukrainian)

- russe (russian)

- grec (greek)

- serbe (serbian)

- croate (croatian)

- arménien (armenian)

- kurde (kurdish)

- turc (turkish)

- arabe (arabic)

- hébreu (hebrew)

- persan (persian)/farsi/parsi

- chinois (chinese)

- japonais (japanese)

- coréen (korean)

- vietnamien (vietnamese)

- thaï (thai)

- hindi

- sanskrit

- urdu

- bengali

- penjabi

- malais (malay)

- cebuano (bisaya)

- haoussa (hausa)

- yoruba/youriba

- lingala

List of political parties in Chile

The political parties of Chile are three clearly categorized, distinct, political groups: the left-wing, the center and the right-wing. Before the 1973 coup, these three political groups were moderately pluralistic and fragmented.

This distinction has existed since the end of the 19th century. Since then, the three groups have been made up of different parties. Each party has had some amount of power in the management of the State or has been represented in the National Congress.

Political parties are recognized legally and formally by Political Constitution of the Republic of Chile of 1980 and by the Organic Constitutional Law of Political Parties of 1987 as organizations that participate in the legal political system and contribute to guiding public opinion.

History of Chile's political parties

Origins and the first blocks (1810–1860)

In Chile, the first political groups were created during the Independence of Chile: the Royalists and the Patriots. The Royalists wanted to maintain the status quo with the King of Spain, while the Patriots wanted to gain a larger degree of freedom. In turn, the Patriots further split into the Moderates, who wanted a slow pace of reform, and the Radicals or Extremists, who favored a much faster pace. All of the early political groups were shy of advocating for full independence since it was unknown if the King would regain his power from Napoleon.

Once Chile gained independence, many political groupings emerged. They were based on various popular leaders during that time, instead of common political ideas. Two very strong political groupings were the Pipolos (liberals) and the Pelucónes (conservatives). Two minor parties, the O’Higginists and the Tobacconists, were often on the Pelucónes' side. After Diego Portales Palazuelos became the architect of the New Institution and the Constitution of 1833, the Pelucónes prevailed for thirty years (1831–1861).

From 1831 to 1861, the prevailing political system was one in which the President co-opted a successor. This system greatly influenced the idea that power should be transferred between members of the ruling political faction. It was only the "Question of the Sacristan" (1856), which divided The Pelucónes, allowed for the rise of the Liberals to power in 1861.

Dominance of the traditional parties (1860–1920)

The formal emergence of political parties in Chilean institutions occurred around the 1850s. Chileans began to challenge the President as the leading role in national political life through the National Congress. In 1891, the disagreement was resolved after a Civil War, in favor of a parliamentary system.

Around that time, the rise of the middle class would eventually lead to the creation of the Radical Party. Their campaign started in the 1850s, as a group defending the interests of the silver mine owners, but it would gradually shift its focus to the employees of the growing state bureaucracy. Soon afterwards, from the same branch of radicalism, the Democratic Party appeared. It was a community that was born closer to the working class segment of society, but that over time would join the game of alliances within the rest of the party system.

After the Chilean Civil War of 1891, the political system began to embody elements of a parliamentary system. Hence, the political coalitions became very strong. Although around twenty distinct political parties and movements existed, Chilean politics was structured around two large groups: the Liberal Alliance (of Liberal and Progressive tendency) and the Coalition (Conservative, Catholics). At the same time, political parties, formerly tools of the upper-class, expanded to include the thriving middle and working classes too.

Expansion of political parties (1920–1973)

With the rise of immigration from Europe, workers with anarchist and socialist ideas came to Chile. Additionally, in the mid-19 century, the union movement began in the nitrate fields of the north of Chile through a surge of the joint labor unions. It is from these processes that in 1912, the Workers' Socialist Party was founded in Iquique by the typographer Luis Emilio Recabarren and 30 union workers and employees. The Workers' Socialist Party is defined as the political party of the Chilean working class. In 1922, the party joined the Third Communist International. Since that date, the party has been known as the Communist Party of Chile.

In the period between 1920 and 1938 (between the start of the first presidential term of Arturo Alessandri Palma and the end of his second term) a series of political incidents led to the loss of the importance of traditional nineteenth-century parties, but for the benefit of the "party masses".

The splendor of this new type of political party would come with the three presidential terms of the Radical Party between 1938 and 1952. At that time, the Radical Party (the faction of the middle class, par excellence), transformed into a large body of positions and political favors, which in the long run would lead to its discredit. Its place as an intermediate political group—between the right and the left—would be taken by the Christian Democratic Party. The Christian Democratic Party is the successor of the National Falange, which in turn had split from the declining Conservative Party after the victory of Eduardo Frei Montalva (1964–1970). Regarding political parties, their main characteristic between 1938 and 1973 was their structuring into the classic "three-thirds" system (right, center, and left).

With Salvador Allende, the Popular Unity came to power as a vast political coalition composed of elements from the center and the left. However, the Military Coup of 1973 signified not only the disappearance of the Popular Unity, but the breakdown of the party system and its end during most of the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. Only in the last year of the military dictatorship was the Organic Constitutional Law of Political Parties enacted, which regulated their formation and function.

Proscription of parties and reorganization (1973–1990)

Between 1973 and 1987, Chilean political parties were prohibited. On October 8, 1973, the members of the Popular Unity were banned and three days later, the rest of the political parties and movements were declared adjourned, and definitively dissolved on March 12, 1977.

On October 1, 1996, the Organic Constitutional Law was published in the Legal Gazette, which re-established the system of electoral registrations and created the Electoral Service of Chile (Servel) as a replacement for the former Directorate of the Electoral Registry. On March 23, 1987, the Organic Constitutional Law of Political Parties was published—which established its objectives, requirements for legalization and the internal organization between others—with which the groups began procedures for their legal recognition.

The National Party was the first political organization to be legally recognized by the Servel on December 23, 1987, inscribed officially in the registry on January 4, 1988. In the following months—before the Plebiscite of October 5, 1988—the National Advance, Humanist, National Renewal, Radical Democracy, Socialist, Christian Democratic (CDP), Party for Democracy, Party of the South, Radical and Green parties were legalized.

Return to democracy (1990–2022)

With the restoration of Democracy in 1990, the prominent political coalition was the Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia (Coalition of Parties for Democracy), a center-left group initially founded by 17 parties, of which the most important, which remained in the coalition throughout the years, were: The Christian Democratic Party, the Socialist Party, the Party for Democracy and the Radical Party. The "Concertación" governed Chile throughout the presidencies of Patricio Aylwin (1990–1994), Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle (1994–2000), Ricardo Lagos (2000–2006) and Michelle Bachelet (2006–2010). The opponent of the ruling coalition, was the Alianza (Alliance). The Alliance was a group of center-right parties, formed by the main parties that supported the "YES" option in the 1988 plebiscite. Extra-parliamentarily, there was the leftist coalition Juntos Podemos Más (Together we can do more), formed by the Communist Party, Humanist Party, PC-AP and others left-wing movements, this coalition did not achieve great electoral results due to the binomial system, which favoured the Concertacion and the alliance.

The "Alliance" came to power when Sebastián Piñera (2010–2014) assumed office. In 2013, after electoral losses, the "Concertación", with the intention of renewing its image, decided to make an agreement with the Communist Party, the Citizen Left, and the MAS Region, creating the New Majority. This coalition won comfortable victories in the 2013 elections and achieved re-election of Michelle Bachelet between 2014 and 2018. In turn, the parties that made up the Alliance, regrouped in 2015 in a new coalition denominated Chile Vamos (Let's go Chile).

In 2016, the number of political parties in Chile doubled, increasing from 14 to 32. It came as a precursor to the municipal elections of the year and the Parliamentary Elections of 2017, given that they will be the first to be held under the new proportional electoral system, the replacement for the binomial system. The binomial system favoured the existence of two blocks to the detriment of isolated parties and independent candidates. In that election, the Frente Amplio (Broad Font) appeared, a coalition that brought together left-wing sectors, which surprisingly won the election of 20 deputies. In the presidential election, Sebastián Piñera was able to return to the government and establish Chile Vamos (Let's go Chile) as an official coalition between 2018 and 2022.

Constitutional Convention and reorganization of coalitions (2022–present)

After the social outburst of 2019, a plebiscite was held that defined the drafting of a new constitution through a Constitutional Convention. The members of that body were elected in May 2021, in a process that benefited independents over political party militants. The most successful group of independents was The List of the People.

From that election, the coalition Apruebo Dignidad (I Approve Dignity) emerged, which gathered the coalitions Frente Amplio (Broad Front) and Chile Digno (Worthy Chile). This group supported the presidential candidacy of Gabriel Boric, who after winning in the ballot decided to summon the Socialist, For Democracy, Radical and Liberal parties to the government, which were grouped in a coalition called Democratic Socialism. This implied the definitive break of the former Concertación/New Majority with the Christian Democratic Party, which was not invited to the new administration.

From the right-wing emerged the Republican Party, which in the parliamentary elections achieved the election of 14 deputies and one senator, facing the traditional center-right grouped in Chile Vamos, which from 2022 went to the opposition after the end of Piñera's government. Other blocks also emerged in those elections, such as the conservative liberal Partido de la gente (Party of the people).

Political parties

This article lists political parties in Chile. Chile has a multi-party system.

Active

As of October 2023 there are 25 legally constituted political parties in Chile.

Historical

- Liberal Party (Partido Liberal) (existed 1849–1966)

- Conservative Party (Partido Conservador) (existed 1851–1949, 1953–1966)

- National Party (Partido Nacional) (existed 1857–1933)

- Democrat Party (Partido Demócrata) (existed 1887–1941)

- Liberal Democratic Party (Partido Liberal Democrático) (existed 1893–1933)

- Democratic Party (Partido Democrático) (existed 1932–1960)

- National Socialist Movement of Chile (Movimiento Nacional Socialista de Chile) (existed 1932–1941)

- Agrarian Labor Party (Partido Agrario Laborista) (existed 1945–1958)

- National Democratic Party (Partido Democrático Nacional) (existed 1960–1999)

- New Democratic Left (founded and dissolved in 1963)

- Socialist Democratic Party (Partido Democrático Socialista) (existed 1964–1965)

- Revolutionary Communist Party (Partido Comunista Revolucionario) (existed 1966–1981)

- National Party (Partido Nacional) (existed 1966–1973, 1983–1994)

- Popular Unitary Action Movement (Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitario or MAPU) (existed 1969–1994)

- Radical Democracy (Democracia Radical) (existed 1969–1990)

- Chilean Social Democracy Party (Partido Socialdemocracia Chilena) (existed 1971–1994)

- Citizen Left (Izquierda Cristiana or Izquierda Ciudadana) (existed 1971–2018)

- National Advance (Avanzada Nacional) (existed 1983–1990)

- Party of the South (Partido del Sur) (existed 1987–1998)

- The Greens (Los Verdes) (existed 1987–1990, 1995–2001)

- Broad Party of Socialist Left (Partido Amplio de Izquierda Socialista or PAIS) (existed 1988–1990)

- Liberal Party (Partido Liberal) (existed 1988–1994)

- Humanist Green Alliance (Alianza Humanista Verde) (existed 1990–1995)

- Union of the Centrist Center (Unión de Centro Centro) (existed 1990–2002)

- National Alliance of Independents (Alianza Nacional de los Independientes) (existed 2001–2006)

- Regionalist Action Party of Chile (Partido de Acción Regionalista de Chile) (existed 2003–2006)

- Independent Regionalist Party (Partido Regionalista Independiente) (existed 2006–2018)

- Broad Social Movement (Movimiento Amplio Social) (existed 2008–2018)

- Progressive Party (Partido Progresista) (existed 2009–2022)

- Amplitude (Amplitud) (existed 2014–2018)

- Citizen Power (Poder Ciudadano) (existed 2015–2019)

- Citizens (Ciudadanos) (existed 2015–2022)

- Common Force (Fuerza Común) (existed 2020–2022)

Alliances

Active

- Chile Vamos, composed of:

- Independent Democratic Union (Unión Demócrata Independiente)

- National Renewal (Renovación Nacional)

- Political Evolution (Evolución Política)

- Government Alliance, composed of:

- Apruebo Dignidad, composed of:

- Democratic Revolution (Revolución Democrática)

- Social Convergence (Convergencia Social)

- Commons (Comunes)

- Communist Party of Chile (Partido Comunista de Chile)

- Social Green Regionalist Federation (Federación Regionalista Verde Social)

- Humanist Action (Acción Humanista)

- Christian Left of Chile (Izquierda Cristiana de Chile)

- Democratic Socialism (Socialismo Democrático), composed of:

- Liberal Party of Chile (Partido Liberal de Chile)

- New Deal (Nuevo Trato)

- Party for Democracy (Partido por la Democracia)

- Radical Party of Chile (Partido Radical de Chile)

- Socialist Party of Chile (Partido Socialista de Chile)

- Apruebo Dignidad, composed of:

Historical

- Popular Front

- Democratic Alliance

- Popular Unity

- Confederation of Democracy

- Concertación

- Alliance

- Coalition for Change

- Juntos Podemos Más

- New Majority

See also

- Lists of political parties

- Timeline of liberal and radical parties in Chile

Notes and references

Bibliography

- Cruz-Coke, Ricardo. 1952. Geografía electoral. Santiago de Chile.

- Donoso, Ricardo. 1946. Las ideas políticas en Chile. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México D.F.

- Edwards, Alberto, y Eduardo Frei. 1949. Historia de la los partidos políticos chilenos. Editorial del Pacífico. Santiago de Chile.

- Friedmann, Reinhard. 1988. 1964–1988 La política chilena de la A a la Z. Melquíades. Santiago de Chile. ISBN 956-231-027-1

- Fuentes, Jordi, y Lía Cortés. 1967. Diccionario político de Chile, 1800–1966'. Santiago de Chile

- Gil, Federico G. 1969, El sistema político de Chile. Editorial Andrés Bello. Santiago de Chile.

- Guilisasti Tagle, Sergio. 1964. Partidos políticos chilenos. Editorial Nascimento. Santiago de Chile.

- Kushner, Harvey: Encyclopedia of Terrorism. California: Sage Publications Ltd., 2003.- ISBN 0-7619-2408-6

- León Echaiz, René. 1939. Evolución histórica de los partidos políticos chilenos. Editorial del Pacífico.

- Urzúa Valenzuela, Germán. 1979. Diccionario político institucional de Chile. Editorial Ariete. Santiago de Chile.

- Urzúa Valenzuela, Germán. 1992. Historia política de Chile y su evolución electoral. Desde 1810 a 1992. Editorial Jurídica de Chile. Santiago de Chile. ISBN 956-10-0957-9

External links

- Servicio Electoral de Chile

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: List of political parties in Chile by Wikipedia (Historical)

- français (french)

- anglais (english)

- espagnol (spanish)

- portugais (portuguese)

- italien (italian)

- basque

- roumain (romanian)

- allemand (german)

- néerlandais (dutch)

- danois (danish)

- suédois (swedish)

- norvégien (norwegian)

- finnois (finnish)

- letton (lettish)

- lituanien (lithuanian)

- estonien (estonian)

- polonais (polish)

- tchèque (czech)

- bulgare (bulgarian)

- ukrainien (ukrainian)

- russe (russian)

- grec (greek)

- serbe (serbian)

- croate (croatian)

- arménien (armenian)

- kurde (kurdish)

- turc (turkish)

- arabe (arabic)

- hébreu (hebrew)

- persan (persian)/farsi/parsi

- chinois (chinese)

- japonais (japanese)

- coréen (korean)

- vietnamien (vietnamese)

- thaï (thai)

- hindi

- sanskrit

- urdu

- bengali

- penjabi

- malais (malay)

- cebuano (bisaya)

- haoussa (hausa)

- yoruba/youriba

- lingala

Communist Party of Chile

The Communist Party of Chile (Spanish: Partido Comunista de Chile, PCCh) is a communist party in Chile. It was founded in 1912 as the Socialist Workers' Party (Partido Obrero Socialista) and adopted its current name in 1922. The party established a youth wing, the Communist Youth of Chile (Juventudes Comunistas de Chile, JJ.CC), in 1932.

History

The PCCh was founded on 4 June 1912 by Luis Emilio Recabarren, after he left the Democrat Party. The party was initially known as the Socialist Workers' Party, before adopting its current name on 2 January 1922.

It achieved congressional representation shortly thereafter and played a leading role in the development of the Chilean labor movement. Closely tied to the Soviet Union and the Third International, the PCCh participated in the Popular Front (Frente Popular) government of 1938, growing rapidly among the unionized working class in the 1940s. It then participated to the Popular Front's successor, the Democratic Alliance.

Concern over the PCCh's success at building a strong electoral base, combined with the onset of the Cold War, led to its being outlawed in 1948 by a Radical government, a status it had to endure for almost a decade until 1958 when it was again legalized. By the 1960s, the party had become a veritable political subculture, with its own symbols and organizations and the support of prominent artists and intellectuals such as Pablo Neruda, the Nobel Prize-winning poet, and Violeta Parra, the songwriter and folk artist. At the time, the U.S. State Department estimated the party membership to be approximately 27,500.

It later came to power along with the Socialist Party in the Unidad Popular ("Popular Unity") coalition in 1970. Within the broad Unidad Popular alliance, the communists sided with Allende, a relative moderate from the Socialist Party, and other more moderate forces of that coalition, supporting more gradual reforms and urging to find a compromise with the Christian Democrats. This line was opposed by more radically leftist factions of the Socialist Party and smaller far-left groups. The party was outlawed after the 1973 coup d'état that deposed President Salvador Allende. Much of the Communist leadership went underground, and for a while the party's moderation continued even after the coup had taken place. Also, it has been argued by Mark Ensalaco that crushing the Communist Party was not a top priority for the military junta. In its first statement after the coup, the party leadership still argued that the coup could succeed because the Unidad Popular was too isolated, due to actions of the 'far-left'. Around 1977, the party changed direction. The Communist Party set up a guerrilla organization, the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front. With the restoration of democracy and the election of a new president in 1990, the Communist Party of Chile was legalized again.

As part of the Popular Unity coalition the PCCh advocated a broad alliance; however, it swung sharply to the left after the 1973 coup, regretting the failure to issue arms to the working class and pursuing an armed struggle against Pinochet's regime. Since the restoration of democracy it has acted independently of its previous partners. Between 1983 and 1987 it was a member of the People's Democratic Movement.

In the 1999/2000 presidential elections the party supported Gladys Marín Millie for the national presidential elections. She won 3.2% of the vote in the first round. At the 2005 legislative election, 11 December 2005, the party won 5.1% of the popular vote, but as a result of Chile's binomial electoral rules, no seats. The small but significant support of the PCCh is believed to have aided in the electoral victories of former socialist president Ricardo Lagos in the 2000 elections, and in the more recent victory of Chile's first female president, the socialist Michelle Bachelet in January 2006, both of whom won in competitive second round runoffs.

From 2013 to 2018, the PCCh was a member of New Majority (Spanish: Nueva Mayoría), a leftist coalition led by Michelle Bachelet.

Controversies

The PCCh faced criticism from several parties in Chile after congratulating Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro on his party's victory in the 2020 parliamentary election. Prominent members of the Party for Democracy, Radical Party, and Socialist Party questioned the PCCh's praise of the election as "flawless", echoing criticisms from opposition parties in Venezuela that the election was neither free nor fair. However, some of its leaders have also publicly condemned the human rights abuses that have taken place in Venezuela under the government of Nicolás Maduro.

Leaders

Electoral performance

- Keys

- RP = supported a candidate from the Radical Party

- SP = supported a candidate from the Socialist Party

- PU–SP = member of the Popular Unity coalition, supported the candidate from the Socialist Party

- PDC = supported a candidate from the Christian Democratic Party

- Ind = supported an independent candidate

- HP = supported a candidate from the Humanist Party

- NM–SP = member of the New Majority coalition, supported the candidate from the Socialist Party

- NM–Ind = member of the New Majority coalition, supported an independent candidate

- AD-SC = member of the Apruebo Dignidad coalition, supported the candidate from Social Convergence

See also

- Communist Youth of Chile

- Luis Emilio Recabarren

- Popular Unity

- Co-ordinating Committee of Communist Parties in Britain

- Juntos PODEMOS Más

- Norte Grande insurrection

Footnotes

Further reading

- Olga Ulianova and Alfredo Riquelme (eds.), Chile en los archivos soviéticos: 1922–1991: Tomo I, Komintern y Chile, 1922–1931 (Chile in the Soviet Archives: Volume 1, Comintern and Chile, 1922–1931). Santiago: Centro de Investigaciones Diego Barros Arana, Lom Ediciones, 2005.

- Olga Ulianova and Alfredo Riquelme (eds.), Chile en los archivos soviéticos: 1922–1991: Tomo II, Komintern y Chile, 1931–1935 (Chile in the Soviet Archives: Volume 2, Comintern and Chile, 1931–1935). Santiago: Centro de Investigaciones Diego Barros Arana, Lom Ediciones, 2009.

External links

- Official website (in Spanish)

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Communist Party of Chile by Wikipedia (Historical)

- français (french)

- anglais (english)

- espagnol (spanish)

- portugais (portuguese)

- italien (italian)

- basque

- roumain (romanian)

- allemand (german)

- néerlandais (dutch)

- danois (danish)

- suédois (swedish)

- norvégien (norwegian)

- finnois (finnish)

- letton (lettish)

- lituanien (lithuanian)

- estonien (estonian)

- polonais (polish)

- tchèque (czech)

- bulgare (bulgarian)

- ukrainien (ukrainian)

- russe (russian)

- grec (greek)

- serbe (serbian)

- croate (croatian)

- arménien (armenian)

- kurde (kurdish)

- turc (turkish)

- arabe (arabic)

- hébreu (hebrew)

- persan (persian)/farsi/parsi

- chinois (chinese)

- japonais (japanese)

- coréen (korean)

- vietnamien (vietnamese)

- thaï (thai)

- hindi

- sanskrit

- urdu

- bengali

- penjabi

- malais (malay)

- cebuano (bisaya)

- haoussa (hausa)

- yoruba/youriba

- lingala

Popular Socialist Party (Chile)

The Popular Socialist Party (Spanish: Partido Socialista Popular, or PSP) was a Chilean left-wing political party that existed between 1948 and 1957. It was the result of the division of the Socialist Party of Chile in 1948 by voting and promulgation of Law No. 8,987 of Defense of Democracy in which the PS was divided in its vote and support among pro-communist and anti-communist.

The anti-communist faction (which were in Bernardo Ibáñez, Oscar Schnake and Juan Bautista Rossetti) supported the law, and the pro-communist (headed by Eugenio González and Raúl Ampuero) refused. The anticommunist group is expelled but makes the Conservative Electoral Registration assign them the name of the Socialist Party of Chile. So the faction led by Ampuero adopted the name Popular Socialist Party.

The party supported the presidential candidacy of Carlos Ibáñez del Campo in 1952. The argument used to support Ibáñez was that it was a popular candidate and needed to drag him from within a truly progressive orientation. When the new government in November 1952, the PSP got the Ministry of Labour with Clodomiro Almeyda. From there, he supported the founding of the Central Workers Union in February 1953. In April 1953, Ibanez reshuffled his cabinet PSP occupying the Ministry of Finance (Felipe Herrera), Labour (Enrique Monti Forno) and Mining (Almeyda). PSP participation in government ends in October 1953.

In 1956, along with other leftist parties, formed the FRAP, which allowed for a rapprochement with the PS. Which led to the 1957 Unity Conference, which reunites the two major factions of Chilean socialism in the Socialist Party of Chile.

Presidential candidates

The following is a list of the presidential candidates supported by the Socialist Party. (Information gathered from the Archive of Chilean Elections).

- 1952: Carlos Ibáñez del Campo (won)

See also

- Socialist Party of Chile

Bibliography

- Cruz-Coke, Ricardo. 1984. Historia electoral de Chile. 1925-1973. Editorial Jurídica de Chile. Santiago

- Fernández Abara, Joaquín. 2007. El Ibañismo (1937-1952). Un Caso de Populismo en la Política Chilena. Instituto de Historia. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Santiago.

- Fernández Abara, Joaquín . 2009. “Nacionalistas, antiliberales y reformistas. Las identidades de la militancia ibañista y su trayectoria hacia el populismo (1937-1952)”, en Ulianova, Olga (Editora): Redes políticas y militancias. La historia política está de vuelta. IDEA-USACH/ Ariadna Editores. Santiago.

- Fuentes, Jordi y Lia Cortes. 1967. Diccionario político de Chile. Editorial Orbe. Santiago.

- Jobet, Julio César. 1971. El Partido Socialista de Chile Ediciones Prensa Latinoamericana. Santiago.

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Popular Socialist Party (Chile) by Wikipedia (Historical)

- français (french)

- anglais (english)

- espagnol (spanish)

- portugais (portuguese)

- italien (italian)

- basque

- roumain (romanian)

- allemand (german)

- néerlandais (dutch)

- danois (danish)

- suédois (swedish)

- norvégien (norwegian)

- finnois (finnish)

- letton (lettish)

- lituanien (lithuanian)

- estonien (estonian)

- polonais (polish)

- tchèque (czech)

- bulgare (bulgarian)

- ukrainien (ukrainian)

- russe (russian)

- grec (greek)

- serbe (serbian)

- croate (croatian)

- arménien (armenian)

- kurde (kurdish)

- turc (turkish)

- arabe (arabic)

- hébreu (hebrew)

- persan (persian)/farsi/parsi

- chinois (chinese)

- japonais (japanese)

- coréen (korean)

- vietnamien (vietnamese)

- thaï (thai)

- hindi

- sanskrit

- urdu

- bengali

- penjabi

- malais (malay)

- cebuano (bisaya)

- haoussa (hausa)

- yoruba/youriba

- lingala

PS

P.S. commonly refers to:

- Postscript, writing added after the main body of a letter

PS, P.S., ps, and other variants may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

- PS Classics, a record label

- P.S. (album), a compilation album of film music by Goran Bregovic

- P.S. (A Toad Retrospective), a compilation album of music by Toad The Wet Sprocket

- "PS", 2003 song by The Books from the album The Lemon of Pink

- "P.S.", 1993 song by James from the album Laid

Other media

- PlayStation, a video gaming brand owned by Sony

- PlayStation (console), a home video game console by Sony

- P.S. (film), a 2004 film

- P.S., a 2010 film by Yalkin Tuychiev

- PS (TV series), a German television series

- PS Publishing, based in the UK

- Prompt corner or prompt side, an area of a stage

- Ponniyin Selvan (disambiguation), Indian media franchise, abbreviated PS

Language

- Pashto language (ISO 639 alpha-2 language code "ps")

- Proto Semitic, a hypothetical proto-language ancestral to historical Semitic languages of the Middle East

- The sound of the Greek letter psi (Greek) (ψ).

Places

- Palau (FIPS PUB 10-4 territory code PS)

- State of Palestine (ISO 3166 country code PS)

Politics

- PS – Political Science & Politics, academic journal

- Parti Socialiste (disambiguation), French

- Partido Socialista (disambiguation), Spanish and Portuguese

- Partito Socialista (disambiguation), Italian

- Polizia di Stato, Italian national police force

- Positive Slovenia

- Pradeshiya Sabha, a unit of local government in Sri Lanka