Search

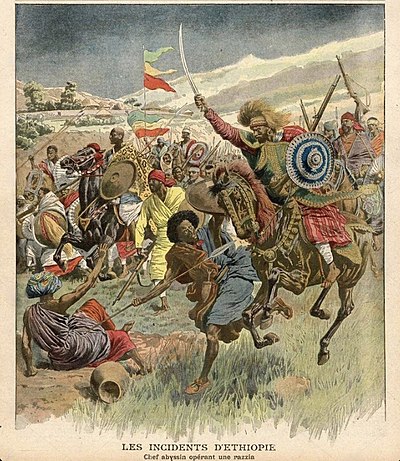

Menelik II's conquests

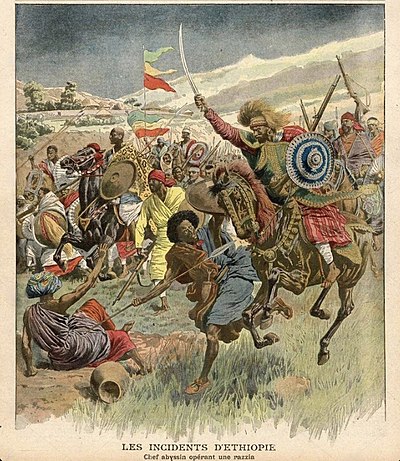

Menelik's conquests, also known as the Agar Maqnat (Amharic: አገር ማቅናት, romanized: ʾägär maqnat, lit. 'Colonization, Cultivation and Christianization of Land'), were a series of expansionist wars and conquests carried out by Emperor Menelik II of Shewa to expand the Ethiopian Empire.

In 1866 Menelik II became the king of Shewa, and in 1878 began a series of wars to conquer land for the Ethiopian Empire and to increase Shewan supremacy within Ethiopia. This was carried out predominantly with soldiers from the Amhara people of Shewa. Menelik is viewed as the founder of modern Ethiopia as a result of the expansion.

Background

After a period of disunity, much of the 19th century saw the reign of two Abyssinian monarchs,Tewodros II (1855-68) and Yohannes IV (1871-89), who progressively centralized the state. The third and last emperor of the century, Menelik II, the King of Abyssinia's Shewa region, managed to bring all of northern Abyssinia under his control and subsequently embarked on a massive expansion of the Ethiopian Empire. From the late 1880s, Menelik dispatched armies and colonists across the west, south, and southeast.

Menelik's expansions coincided with the era of European colonial advances in the Horn of Africa, during which the Ethiopian Empire received significant military resources from foreign powers. France in particular poured in arms into the country during the 1880's, alongside Russia and Italy; seeking to secure favor for protectorate status over the empire. The influx of military equipment facilitated Emperor Menelik's unprecedented campaign of Amhara conquest and expansion. The Emperor conveyed to his European counterparts his 'sacred civilizing mission' to extend the benefits of Christian rule to the 'heathens'. Consequently, the conquered peoples of the south found themselves displaced, often reduced to tenants on their own lands by the new Amhara ruling elite. Menelik became a signatory to the Brussels Act of 1890, which regulated the importation of arms into the African continent. Italy sponsored Ethiopia's inclusion in this act, enabling Abyssinia to "legally" import arms. This move also served to legitimize the arms shipments that had been ongoing for years prior from France. Thus when conflict later began with the Italians during the First Italo-Ethiopian War of 1895-6, the Ethiopian Empire had accrued a significant amount of modern weapons that allowed them to fight on similar terms as the European powers and maintain expansion. British writer Evelyn Waugh describing this nineteenth century event stated:

The process (the creation of the Ethiopian Empire) was closely derived from the European model; sometimes the invaded areas were overawed by the show of superior force and accepted treaties of protection; sometimes they resisted and were slaughtered with the use of modern weapons which were being imported both openly and illicitly in enormous numbers; sometimes they were simply recorded as Ethiopian without their own knowledge.

Menelik's imperial strategy

A system of imperial conquest effectively based on settler colonialism, involving the deployment of armed settlers in newly created military colonies, was widespread throughout the southern and western territories that came under Menelik's dominion. Under the 'Neftenya-Gabbar scheme' the Ethiopian Empire had developed a relatively effective system of occupation and pacification. Soldier-settlers and their families moved into fortified villages known as katamas in strategic regions to secure the southern expansion. These armed settlers and their families were known as the neftenya and peasant farmers who were assigned to them the gabbar. The Neftenya (lit. 'Gun-carrier' or 'Armed settler') were assigned gabbar from the locally conquered population, who effectively worked in serfdom for the conquerors. The feudal obligations imposed on the gabbar were so intensive that they continued to serve the family of a neftegna even after the latter's death.

Though some polities negotiated differing levels of autonomy through tribute payments and taxation, elsewhere local populations were frequently decimated by violent colonial expansions that rested largely on cultural assimilation. Extreme violence was carried out during the conquest of regions like the Kingdoms of Wolaita and Kaffa to the south, along with Illubabor and other territories in the Sudanese borderlands. Military expeditions into the Somali-inhabited Ogaden region under Ras Makonnen were characterized by massacres and expropriation, laying foundations for future incorporation into the Ethiopian Empire. Menelik’s imperialism was culmination of a century of Abyssinian militarization. His army had expanded to such a degree that continual raiding and pillaging became a core feature of the empire, necessary to keep the youthful and armed population preoccupied. University of Oxford Professor of African History Richard Reid observes, "Menelik’s empire was as brutally violent and as reliant on the atrocity-as-method genre of imperialism as the European colonial projects developing apace on Menelik’s borders."

Early conquests

Shewan expansion had started before Menelik, as rulers of the region had started a southward thrust against the Oromo in the early part of the 19th century.

Menelik's first battles to expand the empire occurred when he was still under the nominal authority of Emperor Yohannes IV during the 1870s. With Menelik's incorporations of Wollo to his north during the late 1870s, all of the central region had been consolidated. Menelik dispatched an army against Gojjam to the east and achieved a victory. Emperor Yohannes punished Menelik and the ruler of Gojjam for going to war by taking away parts of their regions, but recognized 'Menelik's right to the south-west.' Having secured the watershed to his south-west, Menelik turn his attention to the Muslim inhabited south-east. During this early period of expansion, Menelik brought the provincial nobility that traditionally dominated Abyssinia under his rule.

Hadiya

In the late 1870s Menelik led a campaign to incorporate the lands of Hadiya which included the Gurage people into Shewa. In 1878, the Soddo Gurage living in Northern and Eastern Gurageland peacefully submitted to Menelik and their lands were left untouched by his armies, likely due to their shared Ethiopian Orthodox faith and prior submission to Negus Sahle Selassie, grandfather of the Emperor. However, in Western Gurage and Hadiya which was inhabited by the Sebat Bet, Kebena, and Wolane fiercely resisted Menelik. They were led by Hassan Enjamo of Kebena who on the advice of his sheiks declared jihad against the Shewans. For over a decade Hassan Injamo fought to expel the Shewans from the Muslim areas of Hadiya and Gurage until 1888 when Gobana Dacche faced him in the Battle of Jebdu Meda where the Muslim Hadiya and Gurage army was defeated by the Shewans, and with that all of Gurageland was subdued.

The Halaba Hadiya however under their chief Barre Kagaw continued to resist until 1893 when the Abyssinians took advantage of the famine that had struck the region and led a conquest into their territory.

Arsi Oromo

Menelik's campaign against the Arsi people of the Oromo were among his bloodiest and most sustained efforts. After a series of military campaigns over several years they were finally subjugated by Shewan firepower.

Conflicts between the Kingdom of Shewa and the Arsi Oromo date back to the 1840s when Sahle Selassie led an expedition against the Arsi. Shewans rulers had longed to pacify and incorporate this territory into their realm. In 1881, Menelik led a campaign against the Arsi Oromo, this campaign proved difficult, as the Oromos abandoned their homeland to wage guerilla war against the Shewan army, the Arsi inflicted significant losses against Menelik's forces through ambushes and raids. Menelik eventually left Arsi territory and his uncle Darge Sahle Selassie was left in charge of the campaign. In September 1886, Darge faced a large Arsi force at the Battle of Azule, the result was an overwhelming Shewan victory as the Arsi Oromo were completely defeated by the Shewan army. After the defeat of the Arsi at Azule the province of Arsi was pacified and Darge was named its governor. After six military campaigns, during 1887 the Arsi finally were brought under the rule of Menelik. After the conquest, much of the best Arsi grazing land was given as war booty to soldiers. Arsi Oromo during the 1960's spoke of the era of Amhara rule beginning after their subjection in 1887 as the start of an 'era of miseries'.

Menelik's military expeditions pushing into southern Ethiopia set a pattern of razing entire districts, killing all male defender and then enslaving the women and children. From the initial raids Menelik and his commanders had seized thousands of prisoners, resulting in an increase in slavery on the domestic and international market. Before the mid-1890's Menelik rarely opposed the slave trade of captives taken during the expansions. Menelik gained half of the plunder and captives taken, while his soldiers and generals divided the rest according to their respective ranks. Despite publicly opposing slavery, Menelik actively supported it during the southern expansions. Four years after the conquest of the Arsi, foreign travelers passing through their regions noted that they were regarded as slaves by the new rulers and in sold openly in markets. The campaigns during 1885 in Ittu Oromo territory that had preceded the occupation of Harar left whole tracts of their territory depopulated.

Annexation of Harar

From 1883 to 1885 the Shewan forces under Menelik attempted to invade the Chercher region of Harar and were defeated by the Ittu Oromo. During 1886, Menelik had started embarking on a large scale campaign to subjugate the south. In 1886 an Italian explorer and his entire party were massacred by soldiers from the Emirate of Harar, giving the Emperor an excuse to invade the Emirate of Harar. The Shewans then led an invasion force, however when this force was camped in Hirna the small army of Emir Abdullah II shot fireworks at the encampment, startling the Shewans and making them flee towards the Awash River during the Battle of Hirna.

Menelik first utilized the significant influx of European arms he received at Harar. The Emperor wrote to European powers: "Ethiopia has been for 14 centuries a Christian island in a sea of pagans. If Powers at a distance come forward to partition Africa between them, I do not intend to remain an indifferent spectator." He did not, sending word to Emir Abdullah, ruler of the historic city of Harar which was pivotal to Muslim East Africa, to accept his suzerainty. The Emir suggested that Menelik should accept Islam. Menelik promised to conquer Harar and turn the principal mosque into a church, saying "I will come to Harar and replace the Mosque by a Christian Church. Await me." The Medihane Alam Church is proof Menelik kept his word.

In 1887 the Shewans sent another large force personally led by Menelik II to subjugate the Emirate of Harar. Emir Abdullah, in the Battle of Chelenqo, decided to attack early in the morning of Ethiopian Christmas assuming they would be unprepared and befuddled with food and alcohol, but was defeated as Menelik had awoken his army early expecting a surprise attack. The Emir then fled to the Ogaden and the Shewans conquered Hararghe. Finally having conquered Harar, Menelik extended trade routes through the city, importing valuable goods such as arms, and exporting other valuables such as coffee. He would place his cousin, Makonnen Wolde Mikael in control of the city. Harari oral tradition recounts 300 Hafiz and 700 newly-wed soldiers killed by Menelik's forces in the short battle. The remembrance of the seven hundred "wedded martyrs" became part of Harari wedding customs to this day, when every Harari groom is given fabric that is called "satti baqla" in Harari, which means "seven hundred." It's a rectangular cloth from white woven cotton ornamented with a red stripe along the edges symbolizing the martyrs' murders. When he presents it, the giver (who usually is the paternal uncle of the woman's father), whispers in the ear of the groom: "So that you do not forget.

The largest Mosque in Harar (known as Sheikh Bazikh, "The capital Mosque," or Raoûf), located in Faras Magala, and the local Madrassa were turned into churches, notably "Medhane Alem church" in 1887 by Menelik II after the conquest.

Conquest of Wolaita and Kaffa kingdoms

Wolaita

In 1890 Menelik invaded the Kingdom of Wolaita. The war of conquest has been described by Bahru Zewde as "one of the bloodiest campaigns of the whole period of expansion", and Wolayta oral tradition holds that 118,000 Welayta and 90,000 Shewan troops died in the fighting. Kawo (King) Tona Gaga, the last king of Welayta, was defeated and Welayta conquered in 1895. Welayta was then incorporated into the Ethiopian Empire. However, Welayta had a form of self-administrative status and was ruled by governors directly accountable to the king until the fall of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974.

Kaffa

The Kingdom of Kaffa was a powerful kingdom located south of the Gojeb river in the dense jungles of the Kaffa mountains. Due to constant invasions from the Mecha Oromos, the Kafficho people developed a very unique defense system unlike anything seen in the Horn of Africa. The Kafficho built very deep trenches (Hiriyoo) and ditches (Kuripoa) along the borders of the kingdom to prevent intruders from entering. They also used natural barriers such the Gojeb River and the mountains to repel invaders. As a result, Kaffa earned a reputation of being impenetrable and inaccessible to outsiders.

In 1895 Menelik II ordered the Kingdom of Kaffa to be invaded and sent three armies led by Dejazmach Tessema Nadew, Ras Wolde Giyorgis and Dejazmach Demissew Nassibu supported by Abba Jifar II of Jimma (who submitted to Menelik) to conquer the mountainous kingdom. Gaki Sherocho the king of Kaffa hid in the hinterlands of his kingdom and resisted the armies of Menelik II until he was captured in 1897 and exiled to Addis Ababa. After the kingdom was conquered Ras Wolde Giyorgis was named its governor.

Expansion into Ogaden

In the first phase of invading the lands to the south inhabited by the Somali people known as Ogaden, Menelik dispatched his troops from newly conquered Harar on frequent raids that terrorized the region. Indiscriminate killing and looting was commonplace before the raiding soldiers returned to their bases with stolen livestock. Repeatedly between 1890 and 1900, Ethiopian raiding parties into the Ogaden caused devastation. The large scale importation of European arms completely upset the balance of power between the Somalis and the Ethiopian Empire, as the colonial powers blocked Somalis from receiving firearms. Many clans in British Somaliland signed the protection treaties with the British in response to Menelik's Invasions, which dictated the protection of Somali rights and the maintenance of independence. Concerning the Ethiopian raids into the Ogaden, British colonial administrator Francis Barrow Pearce wrote in 1898:

The Somalis, although good and brave fighting men, cannot help themselves. They have no weapons except the hide shield and spear, while their oppressors are, as has already been recorded, armed with modern rifles, and they are by no means scrupulous concerning the use of them in asserting their authority…The Abyssinians themselves have no more claim (except that of might) to dominate the wells than a Fiji Islander would have to interfere with a London waterworks company.

However the Ethiopian aggressors were also defeated numerous times by the poorly armed Somalis such as in 1890 near Imi where Makonnen’s troops had suffered a large defeat to Reer Amaden warriors. A British hunter Colonel Swayne, who visited Imi in February 1893, was shown "the remains of the bivouac of an enormous Abyssinian army which had been defeated some two or three years before." In 1897 in order to appease Menelik’s expansionist policy Britain ceded almost half of the British Somaliland protectorate to Ethiopia in the Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1897. Ethiopian authorities have since then based their claims to the Ogaden upon the 1897 treaty and the exchange of letters which followed it. I.M. Lewis argues a subtly different interpretation of this treaty, emphasizing that "the lost lands in the Haud which were excised from the Protectorate [i.e. British Somaliland] were not, however ceded to Ethiopia". Nonetheless Ethiopia exerted no actual influence over the Ogaden east of Jijiga even after the treaty and ruled in name only. When the boundary commission attempted to demarcate the treaty boundary in 1934 the native Somalis were unaware that they were under Ethiopian rule.

Impact and legacy

The incorporation of the southern highlands created unprecedented resources for the imperial core. Before the mid-19th century, Emperor Tewodros II had relied on tribute from the central regions for revenue, but by the start of the 20th century, these same regions provided very little and the majority of state revenue was drawn from the south. Exaction on northern peasants by the imperial state was lightened, and the burden was shifted to the newly ruled southerners. In contrast to imperial expansion into the central and northern highlands, where locals were protected by shared ethnicity and kinship, the people of the south lost most of their traditional lands to the Amhara rulers and were reduced to tenancy on their own lands. The vast southwards expansions carried out by Emperor Menelik exacerbated the divide between the largely Semetic populated north and the primarily Cushitic inhabited south, creating the conditions which encouraged significant future social and political transformations.

In southern Ethiopia, the word Amhara is often treated synonymously to Neftenya, the title given to the soldiers Menelik employed in this period to colonize the people of the south while living off the indigenous population and their lands. The southern expansions and raids fueled a national market for slaves, which Menelik aided and abetted, despite his public proclamations to the contrary.

See also

- Territorial evolution of Ethiopia

- Neftenya

- Scramble for Africa

- Colonisation of Africa

References

Bibliography

- Lewis, I.M., ed. (1983). Nationalism & Self Determination in the Horn of Africa. Ithaca Press.

- Gnamo, Abbas (2014). Conquest and Resistance in the Ethiopian Empire, 1880 - 1974: The Case of the Arsi Oromo. Brill. ISBN 9789004265486.

- Donham, Donald; James, Wendy, eds. (1986). The Southern Marches of Imperial Ethiopia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521322375.

- Abdi, Mohamed Mohamud (2021). A History of the Ogaden (Western Somali) Struggle for Self-Determination: Part I (1300-2007) (2nd ed.). UK: Safis Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906342-39-5. OCLC 165059930.

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Menelik II's conquests by Wikipedia (Historical)

Articles connexes

- Menelik II

- Territorial evolution of Ethiopia

- Neftenya

- Battle of Adwa

- Tewodros II

- Ethiopian Empire

- Oromia–Addis Ababa relations

- Bashah Aboye

- Bafena

- Battle of Dodota

- Yohannes IV

- Tessema Nadew

- First Italo-Ethiopian War

- Solomonic dynasty

- Habte Giyorgis Dinagde

- Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam

- Addis Ababa

- Emperor of Ethiopia

- Battle of Azule

- Lij Iyasu

Owlapps.net - since 2012 - Les chouettes applications du hibou