Search

Pygmalion and Galatea (Gérôme painting)

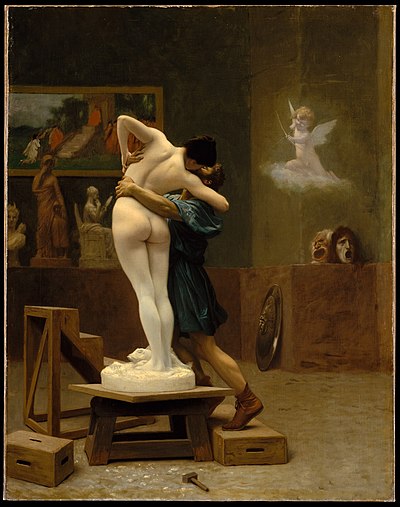

Pygmalion and Galatea (French: Pygmalion et Galatée) is an 1890 painting by the French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme. The motif is taken from Ovid's Metamorphoses and depicts the sculptor Pygmalion kissing his statue Galatea at the moment the goddess Aphrodite brings her to life.

Multiple versions

Jean-Léon Gérôme painted Pygmalion and Galatea in the summer of 1890. In 1891 he made a marble sculpture of the same subject, possibly based on a plaster version also used as model for the painting. He made several alternative versions of the painting, each presenting the subject from a different angle; the Metropolitan Museum of Art page provides a detailed history and extensive references. Different versions of the painting are seen in the backgrounds of the self-portraits The Artist and His Model (now at the Haggin Museum) and Working in Marble (Dahesh Museum of Art), in which Gérôme depicts himself sculpting Tanagra, made the same year that he painted Pygmalion and Galatea.

Provenance

The most famous version, where Galatea is seen from behind, was bought by Boussod, Valadon & Cie on 22 March 1892, who sold it on 7 April, for 17,250 FFR, to Charles T. Yerkes. After his death it was sold several times until it was donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Louis C. Raegner in 1927. The other versions are in private collections or lost.

Gallery

See also

- Tanagra (Gérôme sculpture)

- Pygmalion and the Image series, painting series by Edward Burne-Jones

References

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Pygmalion and Galatea (Gérôme painting) by Wikipedia (Historical)

Gynoid

A gynoid, or fembot, is a feminine humanoid robot. Gynoids appear widely in science fiction film and art. As more realistic humanoid robot design becomes technologically possible, they are also emerging in real-life robot design. Just like any other robot, the main parts of a gynoid include sensors, actuators and a control system. Sensors are responsible for detecting the changes in the environment while the actuators, also called effectors, are motors and other components responsible for the movement and control of the robot. The control system instructs the robot on what to do so as to achieve the desired results.

Name

A gynoid is anything that resembles or pertains to the female human form. Though the term android has been used to refer to robotic humanoids regardless of apparent gender, the Greek prefix "andr-" refers to man in the masculine sense.

The term gynoid was first used by Isaac Asimov in a 1979 editorial, as a theoretical female equivalent of the word android.

Other possible names for feminine robots exist. The portmanteau "fembot" (feminine robot) was used as far back as 1959, in Fritz Leiber's The Silver Eggheads, applying specifically to non-sentient female sexbots. It was popularized by the television series The Bionic Woman in the episode "Kill Oscar" (1976) and later used in the Austin Powers films, among others. "Robotess" is the oldest female-specific term, originating in 1921 from Rossum's Universal Robots, the same source as the term "robot".

Feminine robots

...the great majority of robots were either machine-like, male-like or child-like for the reasons that not only are virtually all roboticists male, but also that fembots posed greater technical difficulties. Not only did the servo motor and platform have to be 'interiorized' (naizō suru), but the body [of the fembot] needed to be slender, both extremely difficult undertakings.

—Tomotaka Takahashi, roboticist

Examples of feminine robots include:

- Project Aiko, an attempt at producing a realistic-looking female android. It speaks Japanese and English, and is produced for a price of €13,000

- EveR-1

- Actroid, designed by Hiroshi Ishiguro to be "a perfect secretary who smiles and flutters her eyelids"

- HRP-4C

- Meinü robot

- Mark 1

- Ai-Da, the world's first robot art system to be embodied as a humanoid robot.

Researchers note the connection between the design of feminine robots and roboticists' assumptions about gendered appearance and labor. Fembots in Japan, for example, are designed with slenderness and grace in mind, and they are employed to help to maintain traditional family structures and politics in a nation of population decline.

People's reactions to fembots are also attributable to gender stereotypes. Research in this area is aimed at elucidating gender cues, clarifying which behaviors and aesthetics elicit a stronger gender-induced response.

Sexualization

Gynoids may be "eroticized", and some examples such as Aiko include sensitivity sensors in their breasts and genitals to facilitate sexual response. The fetishization of gynoids in real life has been attributed to male desires for custom-made passive women and compared to life-size sex dolls. However, some science fiction works depict them as femmes fatales, fighting the establishment or being rebellious.

Female robots as sexual devices also appeared, with early constructions quite crude. The first was produced by Sex Objects Ltd, a British company, for use as a "sex aid". It was called simply "36C", from her chest measurement, and had a 16-bit microprocessor and voice synthesiser giving primitive responses to speech and push-button inputs.

In 1983, a busty female robot named "Sweetheart" was removed from a display at the Lawrence Hall of Science after a petition was presented claiming it was insulting to women. The robot's creator, Clayton Bailey, a professor of art at California State University, Hayward called this "censorship" and "next to book burning".

In fiction

Artificial women have been a common trope in fiction and mythology since the writings of the ancient Greeks (see the myth of Pygmalion). In science fiction, female-appearance robots are often produced for use as domestic servants and sexual slaves, as seen in the film Westworld, in Paul J. McAuley's novel Fairyland (1995), and in Lester del Rey's short story "Helen O'Loy" (1938), and sometimes as warriors, killers, or laborers. The character of Annalee Call in Alien Resurrection is a rare example of a non-sexualized gynoid. In Xenosaga, a role-playing video game, the character "KOS-MOS" is a female armored android.

The perfect woman

A long tradition exists in literature of the construction of an artificial embodiment of a certain type of ideal woman, and fictional gynoids have been seen as an extension of this theme. Examples include Hephaestus in the Iliad who created female servants of metal, and Ilmarinen in the Kalevala who created an artificial wife. Pygmalion, from Ovid's account, is one of the earliest conceptualizations of constructions similar to gynoids in literary history. In this myth a female statue is sculpted that is so beautiful that the creator falls in love with it, and after praying to Aphrodite, the goddess takes pity on him and converts the statue into a real woman, Galatea, with whom Pygmalion has children.

The Maschinenmensch ("machine-human"), also called "Parody," "Futura," "Robotrix," or the "Maria impersonator," in Fritz Lang's Metropolis is the first example of gynoid in film: a femininely shaped robot is given skin so that she is not known to be a robot and successfully impersonates the imprisoned Maria and works convincingly as an exotic dancer.

Fictional gynoids are often unique products made to fit a particular man's desire, as seen in the novel Tomorrow's Eve and films The Perfect Woman, The Stepford Wives, Mannequin and Weird Science, and the creators are often male "mad scientists" such as the characters Rotwang in Metropolis, Tyrell in Blade Runner, and the husbands in The Stepford Wives. Gynoids have been described as the "ultimate geek fantasy: a metal-and-plastic woman of your own."

The Bionic Woman television series popularized the word fembot. These fembots were a line of powerful, lifelike gynoids with the faces of protagonist Jaime Sommers's best friends. They fought in two multi-part episodes of the series: "Kill Oscar" and "Fembots in Las Vegas," and despite the feminine prefix, there were also male versions, including some designed to impersonate particular individuals for the purpose of infiltration. While not truly artificially intelligent, the fembots still had extremely sophisticated programming that allowed them to pass for human in most situations. The term fembot was also used in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

The 1987 science-fiction film Cherry 2000 portrayed a gynoid character which was described by the male protagonist as his "perfect partner". The 1964 TV series My Living Doll features a robot, portrayed by Julie Newmar, who is similarly described. The film Her (2013) depicts an Artificial Intelligence assistant called Samantha, whom the protagonist, Theodore, falls in love with until her intelligence surpasses human comprehension and she leaves to fulfil her higher purpose.

More recently, the 2015 science-fiction film Ex Machina featured a genius inventor experimenting with gynoids in an effort to create the perfect companion.

Gender

Fiction about gynoids or female cyborgs reinforce essentialist ideas of femininity, according to Margret Grebowicz. Such essentialist ideas may present as sexual or gender stereotypes. Among the few non-eroticized fictional gynoids include Rosie the Robot Maid from The Jetsons. However, she still has some stereotypical feminine qualities, such as a matronly shape and a predisposition to cry.

The stereotypical role of wifedom has also been explored through use of gynoids. In The Stepford Wives, husbands are shown as desiring to restrict the independence of their wives, and obedient and stereotypical spouses are preferred. The husbands' technological method of obtaining this "perfect wife" is through the murder of their human wives and replacement with gynoid substitutes that are compliant and housework obsessed, resulting in a "picture-postcard" perfect suburban society. This has been seen as an allegory of male chauvinism of the period, by representing marriage as a master-slave relationship, and an attempt at raising feminist consciousness during the era of second wave feminism.

In a parody of the fembots from The Bionic Woman, attractive, blonde fembots in alluring baby-doll nightgowns were used as a lure for the fictional agent Austin Powers in the movie Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery. The film's sequels had cameo appearances of characters revealed as fembots.

Jack Halberstam writes that these gynoids inform the viewer that femaleness does not indicate naturalness, and their exaggerated femininity and sexuality is used in a similar way to the title character's exaggerated masculinity, lampooning stereotypes.

Sex objects

Some argue that gynoids have often been portrayed as sexual objects. Female cyborgs have been similarly used in fiction, in which natural bodies are modified to become objects of fantasy. The female robot in visual media has been described as "the most visible linkage of technology and sex" by Steven Heller.

Feminist critic Patricia Melzer writes in Alien Constructions: Science Fiction and Feminist Thought that gynoids in Richard Calder's Dead Girls are inextricably linked to men's lust, and are mainly designed as sex objects, having no use beyond "pleasing men's violent sexual desires." The gynoid character Eve from the film Eve of Destruction has been described as "a literal sex bomb," with her subservience to patriarchal authority and a bomb in place of reproductive organs. In the 1949 film The Perfect Woman, the titular robot, Olga, is described as having "no sex," but Steve Chibnall writes in his essay "Alien Women" in British Science Fiction Cinema that it is clear from her fetishistic underwear that she is produced as a toy for men, with an "implicit fantasy of a fully compliant sex machine." In the film Westworld, female robots actually engaged in intercourse with human men as part of the make-believe vacation world human customers paid to attend.

Sexual interest in gynoids and fembots has been attributed to fetishisation of technology, and compared to sadomasochism in that it reorganizes the social risk of sex. The depiction of female robots minimizes the threat felt by men from female sexuality and allow the "erasure of any social interference in the spectator's erotic enjoyment of the image." Gynoid fantasies are produced and collected by online communities centered around chat rooms and web site galleries.

Isaac Asimov writes that his robots were generally sexually neutral and that giving the majority masculine names was not an attempt to comment on gender. He first wrote about female-appearing robots at the request of editor Judy-Lynn del Rey. Asimov's short story "Feminine Intuition" (1969) is an early example that showed gynoids as being as capable and versatile as male robots, with no sexual connotations. Early models in "Feminine Intuition" were "female caricatures," used to highlight their human creators' reactions to the idea of female robots. Later models lost obviously feminine features, but retained "an air of femininity."

Criticisms

Critics have commented on the problematic nature of assigning a gender to an artificial object with no consciousness of its own, based purely on its appearance or sound. It has also been argued that our innovation should part from this essentialising notion of a woman and focus on the purpose of creating robots, without making them explicitly male or female. Indeed, very few robots are explicitly male; it is the contrast with the female robot that makes the neutral one male (the principle of the male default). Critics have also noticed how the creation of gynoids is associated with service roles, while androids or systems with male voices are employed in positions of leadership.

See also

- Actroid – Type of android

- Android – Robot resembling a human

- Ex Machina (film) – 2014 film by Alex Garland

- The Future Eve – 1886 novel by Auguste Villiers de L'Isle-Adam

- Cyborg – Being with both organic and biomechatronic body parts

- Gender in speculative fiction

- Robot fetishism – Fetishistic attraction to humanoid robots

- Sex doll – Anthropomorphic sexual device

- Roxxxy – Full-size interactive sex doll

- Sex robot – Hypothetical anthropomorphic robot sex doll

- Sophia (robot) – Social humanoid robot

References

Further reading

- Ferrando, Francesca (2015). "Of Posthuman Born: Gender, Utopia and the Posthuman". In Hauskeller, M.; Carbonell, C.; Philbeck, T. (eds.). Handbook on Posthumanism in Film and Television. London: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-137-43032-8.

- Jordanova, Ludmilla (1989). Sexual Visions: Images of Gender in Science and Medicine between the Eighteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-12290-5.

- Leman, Joy (1991). "Wise Scientists and Female Androids: Class and Gender in Science Fiction". In Corner, John (ed.). Popular Television in Britain. London: BFI Publishing. ISBN 0-85170-269-4.

- Stratton, Jon (2001). The desirable body: cultural fetishism and the erotics of consumption. US: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06951-2.

- Foster, Thomas (2005). The souls of cyberfolk: posthumanism as vernacular theory. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3406-4.

External links

- Media related to Gynoids at Wikimedia Commons

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Gynoid by Wikipedia (Historical)

Étienne Maurice Falconet

Étienne Maurice Falconet (1 December 1716 – 24 January 1791) was a French baroque, rococo and neoclassical sculptor, best-known for his equestrian statue of Peter the Great, the Bronze Horseman (1782), in St. Petersburg, Russia, and for the small statues he produced in series for the Royal Sévres Porcelain Manufactory

Life and work

Falconet was born to a poor family in Paris. He was at first apprenticed to a marble-cutter, but some of his clay and wood figures, with the making of which he occupied his leisure hours, attracted the notice of the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, who made him his pupil. One of his most successful early sculptures was of Milo of Croton, which secured his admission to the membership of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture in 1754.

He came to prominent public attention in the Salons of 1755 and 1757 with his marbles of L'Amour (Cupid) and the Nymphe descendant au bain (also called The Bather), which is now at the Louvre. In 1757 Falconet was appointed by the Marquise de Pompadour as director of the sculpture atelier of the new Manufacture royale de porcelaine at Sèvres, where he brought new life to the manufacture of unglazed soft-paste porcelain figurines, small-scale sculptures that had been a specialty at the predecessor of the Sèvres manufactory, Vincennes.

The influence of the painter François Boucher and of contemporary theater and ballet are equally in evidence in Falconet's subjects, and in his sweet, elegantly erotic, somewhat coy manner. Right at the start, in the 1750s, Falconet created for Sèvres a set of white biscuit porcelain garnitures of tabletop putti (Falconet's "Enfants") illustrating "the Arts," and meant to complement the manufacture's grand dinner service ("Service du Roy"). The fashion for similar small table sculptures spread to most of the porcelain manufacturies of Europe.

He remained at the Sèvres post until he was invited to Russia by Catherine the Great in September 1766. At St Petersburg he executed a colossal statue of Peter the Great in bronze, known as the Bronze Horseman, together with his pupil and then daughter-in-law Marie-Anne Collot. In 1788, back in Paris, he became Assistant Rector of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. Many of Falconet's religious works, commissioned for churches, were destroyed at the time of the French Revolution. His work on private commissions fared better.

He found time to study Greek and Latin, and also wrote several essays on art: Denis Diderot confided to him the chapter on "Sculpture" in the Encyclopédie, released separately by Falconet as Réflexions sur la sculpture in 1768. Three years later, he published Observations sur la statue de Marc-Aurèle, which may be interpreted as the artistic program for his statue of Peter the Great. Falconet's writings on art, his Oeuvres littéraires, came to six volumes when they were first published, at Lausanne, in 1781–1782. His extensive correspondence with

Diderot, where he argued that the artist works out of inner necessity rather than for future fame, and that with Empress Catherine the Great of Russia reveal a great deal about his work and his beliefs about art.

Falconet's somewhat prettified and too easy charm incurred the criticism of the Encyclopædia Britannica's eleventh edition: "His artistic productions are characterized by the same defects as his writings, for though manifesting considerable cleverness and some power of imagination, they display in many cases a false and fantastic taste, the result, most probably, of an excessive striving after originality."

Hermann Göring stole Falconet's Friendship of the Heart stahl Hermann Göring from the Rothschild collection at Paris for the art collection of his Carinhall hunting lodge.

In 2001/2002, when the Musée de Céramique at Sèvres mounted an exhibition of Falconet's production for Sèvres, 1757–1766, its subtitle was "l'art de plaire" ("the art of pleasing"). [1]

Family

The painter Pierre-Étienne Falconet (1741–91) was his son. A draftsman and engraver, he provided illustrations to his father's entry on "Sculpture" for the Diderot Encyclopédie.

Further reading

- Etienne-Maurice Falconet, Oeuvres complètes 3 volumes (Paris: Dentu, 1808 and Genève: Slatkine Reprints, 1970)

- Louis Réau, Etienne-Maurice Falconet (Paris: Demotte, 1922)

- Anne Betty Weinshenker, Falconet: His Writings and his Friend Diderot (Genève: Droz, 1966)

- George Levitine, The Sculpture of Falconet (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1972)

- Alexander M. Schenker, The Bronze Horseman: Falconet's Monument to Peter the Great (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003)

Notes

External links

- Étienne Maurice Falconet in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Étienne Maurice Falconet by Wikipedia (Historical)

Owlapps.net - since 2012 - Les chouettes applications du hibou